by Hannah Wilson

Web, Blog and Social Media Coordinator, British Association for Holocaust Studies

“Why shouldn’t I be happy? Whatever Hitler tried to do, I’ve got six grandchildren, two daughters, three great grandchildren. Why shouldn’t I enjoy life? And I do enjoy life, I always did.” – Zigi Shipper

A short time ago, I was invited to the home of Zigi Shipper: a survivor of the Łódź Ghetto, Auschwitz- Birkenau and Stutthof concentration camp. A sweet, friendly, and exceptionally warm man, Zigi was immediately welcoming and openly shared his life with me. I did not need to ask many so many questions; the details came back to Zigi like it had only happened yesterday. So, I listened, and I learned.

There were tears, but there was laughter too. Such is the wonderful, life affirming nature of Zigi. Though he will be ninety-one years old this year, he spoke for hours with passion and vigour, in the company of his wife Jeanette. I realised just how much he had been through, both during and after the war. After years of speaking publicly and contributing to Holocaust education in the UK, Zigi was awarded the British Empire Medal, and his work is continued by his children and grandchildren, who also work to preserve the memory of those who suffered.

In honour of this years Holocaust Memorial Day theme, we are proud to have Zigi as our “Light in the Darkness” and to share his story- in his own words.

__________________________________________________________________________________

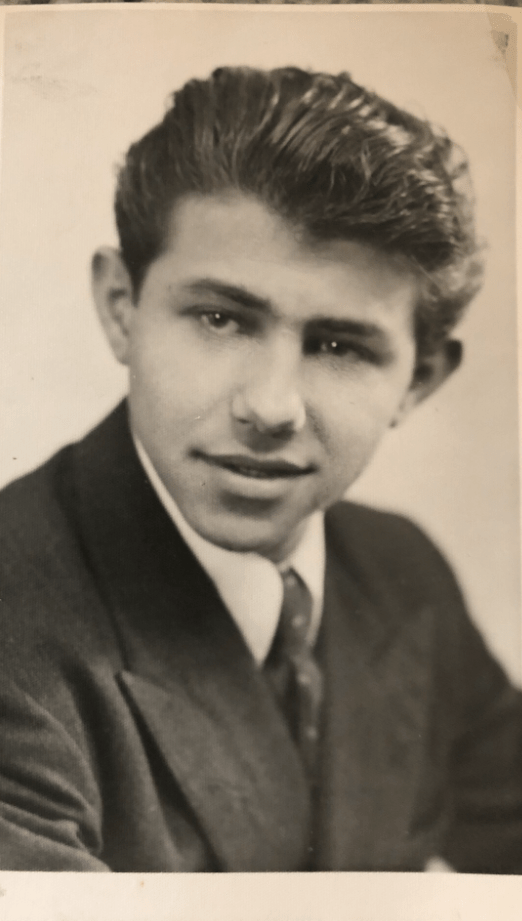

Zigi (Zygmunt) Shipper BEM was born in 1930 in Łódź, Poland. He grew up with his father and grandparents after his parents divorced when he was just a child. He had a happy and comfortable childhood, attending a Jewish school and spending time with his cousins and friends.

Life Before the War

Hannah: Ziggy, I’d like to know a bit about your life before the Holocaust. I know you were relatively young before the war broke out and the invasion of Poland in 1939:

Zigi: Well, after my mother decided to leave home when I was three years old, I had a very good life with my grandparents who brought me up. Not my father, because he had to work. My grandparents were Orthodox Jews and we had a good life, and a nice apartment in the city of Łódź. I even had my own bedroom. My grandfather had a business and my father and uncle worked for him too.

I went to school like every child, all very normal. It was a Jewish school. And everything was alright, until I was about nine and half years old…then all of a sudden, the war began. About six weeks later, the whole of Poland was occupied by Germany. Then, everything changed.

First of all, a Jewish child wasn’t allowed to go to school, and a Jewish teacher wasn’t allowed to teach. Doctors, lawyers, and accountants weren’t allowed to practice their professions, and it carried on like that. Every morning there would be new posters up saying : ‘You mustn’t do this, you mustn’t do that”, or “you mustn’t travel on the trams”. If they found a Jewish man who they could recognise, you know – with the beard, or the way he was dressed, they used to sling him off the tram. Some people didn’t care, they used to want to sling him off, regardless of if you were stationary or moving. Stupid stuff like that. Then one morning, we were told we had to wear the Star of David. To be honest, for us children we were quite happy with it, we didn’t care. We didn’t quite understand what it meant, like it did for the adults.

Establishment of the Ghetto

In early February 1940, the Germans established a ghetto in the north-eastern section of Łódź. About 160,000 Jews, more than a third of the city’s population, were forced into one small area, to live in appalling living conditions.

Hannah: Can you tell me how life changed for you after the ghetto was established?

Zigi: So, the SS who were in charge announced that every single Jew living in Łódź had to go to a designated living area, which was the poorest area of town. But Łódź had one of the biggest Jewish communities in Poland, so it was a big problem. They told us that if any Jewish person – it doesn’t matter they are a man or woman- didn’t go there by April 1st, they would be killed. So, after living in a three-bedroom apartment with my grandparents, we now had one solitary room with no running water, no toilet and no choice.

Hannah: It must have been confusing, to be so young and the world you know changing so rapidly around you.

Zigi: You know, when things are like that, you have to get to know better and quickly. You haven’t got enough to eat, you are cold, and you don’t really understand why. I was in one room with my Grandparents, and early one morning my father came to me and told me he’s going to run away because if the Germans came, they would kill him. But he told me: they won’t hurt children. During WW1, only the grown-ups had problems, not the children. Anyway, he ran away, and I found out that he ended up in Russia.

We were already in the ghetto when it was closed off in April 1940. We were told that we all had to go to work; if we don’t work, we don’t get any food. Inside the ghetto, it was mainly run by Jewish people. We called them the Jewish police. The fences of the ghetto weren’t electrified, so sometimes people could run out, but very few people could escape. Sometimes us kids used to sit down near the fence and hope to see a Polish horse and carriage, and maybe they’ll have some vegetables for us. If we saw one, we started screaming, and sometimes the Germans even looked away when he might throw it to us. Though some of them used to hit us with their rifles. If we managed to get food, the Jewish Police would take it away because we weren’t allowed extra, but I think they took it for themselves, you know? Honestly, we hated them as much as we hated the Germans.

So, when everyone had to go to work my Grandmother got a job in tailoring, producing clothing for the German army, and I got in a metal factory also producing things for the Germans. My grandfather was already very ill because he wouldn’t eat anything, and after a short time he died, and just left us two. She worked, and I worked for the first time in my life. I was just ten years old, working from seven in the morning until seven in the evening. At lunchtime, we got a soup like water with a few vegetables. For the children, sometimes they would dig a little deeper, sometimes there was even a piece of meat. Of course, it was horsemeat! Whenever I say that now to children in schools, they ask me: how could I eat it?! I tell them: when you are starving, you’ll eat anything, and I hope you’ll never find that out! These children do not know starving and thank God for that.

At home we hardly had any food, there was hardly anything left. We couldn’t understand. We were working for the Germans, so why couldn’t they give us more food? So, a lot of people were dying, from lack of food or from starvation. They were dying from many other illnesses too, and although we had some doctors, the medicine wasn’t there. A lot of people were committing suicide, and I couldn’t understand; I kept asking my Grandmother: “Why are they killing themselves?”, and she never told me. But now I realise. Can you imagine, being a mother and losing your children from starvation….or lack of medication? You see, with the Germans, especially the SS, you’ve got to remember that children were useless to them. If they can’t work, then they’re useless! And it carried on like that.

Round Ups

Hannah: What happened after the Germans started to round up Jews from the Ghetto?

Zigi: One day, the SS came and spoke to the Jewish authorities who were running the ghetto, and said they need seventy thousand people to go to Germany to work. They asked the Jewish police to do it, although they didn’t want to. So, they said: “Okay! We’ll do it ourselves, and we will go from house to house and take the people we want”. They said they’d let us know the night before if they were coming to our district. My Grandmother said she wanted to hide me, and to come with her. I said: Why do I need to come with you? I was twelve years old then, but I look about nine, so I assumed that they won’t take me to work! So, I went to sleep. And in the morning, I woke up and went downstairs. There were big lorries and SS men started taking people, and so they took me as well.

They slung me onto the lorry, and when I looked inside, I couldn’t believe it. There were old people, disabled people, children, women with babies. You know, all of my life, I’ve always been lucky. And I got an uneasy feeling, so I jumped off the lorry.

Hannah: So, judging by the kind of people who were in the lorry, did you begin to realise than they probably are not being taken to work?

Well look, I was twelve years old and I knew about the killings already, you know? So, I jumped off and I ran and ran, and hid myself in a house. Stayed there all night and eventually went back, and the funny thing is that one of my cousins had also hidden himself. He also survived the war and later became a Rabbi in Jerusalem, Israel. So, he and I continued to work in the ghetto as before. I don’t know how we managed to survive, but we always had friends, who managed to steal things or who we managed to also share with.

And everything continued like that until I was fourteen. They SS came and said the Russians are very near Warsaw, so that’s why they have to liquidate the ghetto. Then, the people who were working in the factory were taken off to Germany to work. You could choose to go with the people you were living with, with so I asked my Grandma and she agreed. We could take one suitcase. Where were going, we don’t need anything else, they told us. So, we went back to the workplace, and they told us to report to the railway station the next morning.

Transports

Hannah: Can you tell me about what happened that morning?

Zigi: We came to the station, with our cases. I said to my grandmother: I can’t see any trains! She said, but they’re standing right in front of you. But I thought – they’re not for human beings, they’re for cattle or something and she said – that’s all there is.

They opened the doors, and they put the people in. They were so high they had to help to lift us up, and they had a problem shutting the doors because there were so many people. You couldn’t sit down – if you sat down, you died because people were on top of you. A few years ago, I was talking to my daughters and I said to them: you know, something has always worried me to this day, and I can’t get it out of my head… how can a child of fourteen hope that people would die so that he could have somewhere to sit down? What has become of me? I was completely dehumanised.

So afterwards, when they had taken us away to work, we thought about the people left behind in the ghetto. We never got a letter or anything, but we knew that they had taken them to be killed. What could I do? Nothing.

Off the train, before we came off, I looked through the small windows in the car. I saw the word ‘Auschwitz”. It didn’t mean anything to me, but underneath I saw the word Oświęcim. That’s Polish. Someone shouted out, it’s a small little place near Krakow. Once we stopped, they opened the doors and told us to leave everything, because everyone is going to the showers. We were one of the few transports that arrived at Auschwitz with a named list – they called out our names and we went to one side. There were other people however, that went through a selection.

Arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau and Selections

Hannah: What happened during the selection process?

Zigi: At the selections, they invited people to go left, left again. These were older people, or women holding babies. They asked them to put the baby down and go to one side. Can you imagine, a mother leaving her baby? They wouldn’t do it!

Hannah: It sounds like it would have been such a confusing and chaotic situation, that began to incite fear in a lot of people?

Zigi: Yes it was – and in some cases they would just kill the woman and kill the child, several times only the child. Eventually, they took those on the left to a room, a place. An SS guard closed the door, one went to the back of the building and poured in some Zyklon B gas. Within twenty minutes everybody in that room was dead. Women, men, children, disabled, older people. And you know even up to today I want to ask – how can a human being do that as part of their working day, and then sit down to have his dinner with his wife and children, ten meters or less from a gas chamber?! And seeing people hanging…

As for us, eventually, they took us to the actual showers and shaved everyone.

Hannah: Were you separated from your Grandmother?

Zigi: Yes, the women went separately. So, they shaved the hair, we had a shower and they put disinfectant on us. When we undressed, they said we would get everything back, but when I came out, they gave us the striped pyjamas. I’m sure you’ve seen them. They gave us numbers but didn’t tattoo them. My number was 84303. I will never forget that number – I forget my debit and credit card, but I will never forget that bloody number!

Life in Auschwitz

Hannah: What were those first weeks like for you in Auschwitz?

Zigi: We had no choice, and eventually they took us to the barracks. They said we are lucky, we were only one hundred and fifty people, so we were only three to a bunk. But you’ve seen those bunks, not fit for humans. They told us we’d get our dinner in the evening, but they didn’t say anything about lunch. When the dinner came, it was a piece of bread and black coffee. I didn’t even know what coffee was, in Poland we mostly drank tea. But this coffee wasn’t even real coffee, so drunk very little, it was bitter and horrible.

We went to sleep we got up in the morning, we expected bread, but we had to go outside to be counted. People were missing- but they were still in the bunks. Some were dead, some were too ill. Some people ran to the electric wires around the camp because they didn’t want to live- they’d lost their wives, children and parents.

Hannah: Did you realise immediately once you had arrived that people were being killed in gas chambers?

Zigi: No, I only realised one day later. We found out through the people who were working there sorting through the clothing and belongings that they had taken away from us, who were Jewish people in Birkenau. They looked for valuables. When we came there and saw the chimneys we thought: Oh, it must be good there, they bake their own food! But the next day, when we met with these other people we realised.

Anyway, when we got up in the morning and the guards went inside and removed people who were ill, they said they’re taking them to hospital. It was hardly a hospital, and we all heard of Dr. Mengle, the biggest killer there. He would throw babies into ice cold water to see how long they could live. What people can do…when I think about that, and how civilised Germany was before the war…there was such a big change in how they saw Jews. And they never found him after the war.

So yes, within one day we more or less knew what happened there. We were lucky, we stayed in Auschwitz I for about six weeks. People at Birkenau weren’t so lucky….there were more gas chambers there. We just had one small one in this part of the camp. When I went back to Poland after the war, I saw things in Auschwitz that I couldn’t believe – I didn’t see it at the time.

Stutthof Concentration Camp

Zigi: So, after six weeks in Auschwitz, they took us to Stutthof, and again separated the men and women. This was the only place at which I said to my friends, here I am going to die. It was November in Poland, the weather was well below zero. We had to huddle together to keep warm.

I didn’t know where I was or what I was doing, but I was sure I was going to die. One day, an SS man came and said they need twenty boys to go to work on a railway line. I volunteered, and they said they will come for us in a few days’ time. The grownups asked me, why did you volunteer? They will probably kill you! I said, well I’m going to die here anyway so what’s the difference?

Hannah: It seems like you had accepted or expected death by this point?

Zigi: Exactly. Three days later they came and took us on ordinary passenger trains! So, we couldn’t believe it. We arrived at a camp with fifteen hundred people there, all Jewish. A lot were from Rome, Italian Jews. As we worked on the railway, there was actually a chance to steal food, vegetables and fruit. The guards were more relaxed, and even the little camp was warmer, and we weren’t cold. One day, some of the boys stole some tobacco which was on its way to the German army fighting the Russians- we weren’t so far from Russia. They caught them and kept them in a room for a week without food and water. After the week, they told us to come and see these boys. There were gallows set up with ropes hanging and stools underneath. The German officers lined these boys up – they were older than us, we were too young to smoke. They read out their names and prisoner numbers, and why they deserved death. But the boys jumped off on their own. I ask another prisoner, why did they do that? He replied- they didn’t want to give the Germans the satisfaction of killing them.

We went back to work and stayed there. The Russians were getting nearer, so they eventually took us back to Stutthof for a short time. Unfortunately, I was very ill with typhus, I needed medication and water but they had none. Somehow, I was surviving but very unwell. Afterwards, I found out it was a deadly disease. One day, they came and said they’d take us to Germany. But we have to go via Poland first. They came with buses, but then from the Polish part we would have to walk.

Death March

Hannah: How did you survive the death march, being so ill?

Zigi: My friends helped me to walk, and we went to a port. They held us there they held us on a boat with no water, people died, and they threw people into the sea. One evening, we had Danish and Norwegian prisoners of war arrive. Their barge was standing, so we figured we must be near land because the German guards would leave for the night. Eventually they took us onto land. We didn’t know where we were, so we stayed and the guards came and said were not putting you onto the boat, we’re going to another port ten miles away. I couldn’t make it! It was a death march.

My friends helped me, and we walked and walked. They took us to Neustadt, a German Naval Town. Shooting was all around, they killed those who became weak. We arrived and saw huge boats and ships at the new port- two were full of prisoners, we would go on the third, which they said would eventually take us to Denmark. But we knew what would happen- they would take these boats out to sea and explode them. We heard planes flying, and we knew it must be the allies!

As we sat and waited for something to happen, we prayed they could start bombing. And they did! They hit one of the prisoner boats, on that we were meant to be on. People were jumping from it, mostly to their death. Some survived. The bombing stopped, we waited more. Someone said, look around you.

Liberation

Hannah: Please tell me about the liberation, Zigi. It must have felt unbelievable!

Zigi: Yes, we saw tanks with British soldiers, 3rd May 1945. We had been liberated by the British army. I crawled out on all fours, I needed water. I couldn’t speak English so shouted “wasser” in German and a British soldier threw me some down with a little box of food. I had people on top of me, but my friends managed to save me from the mob. There was bread etc. We were sitting waiting, not long. The officers said: “you are free now, you don’t have to worry. You are in a German port but there is no German here. So, go and help yourself, we have masses of food.” We got tins of meat, fruit. Lots of it was brand new to me- like pineapple! In a tin, I couldn’t understand it. Unfortunately for the British Army, this wasn’t a good idea. We were starving, and they gave us such rich food. We should have had it bit by bit, but they didn’t know! People were lying on the ground struggling to digest it, some even died.

My friends and I found an old prison to rest in. I had a sheet and a bunk bed with a white sheet. When I woke up in was black! I couldn’t remember the last time I washed- three months ago? Six months? It wasn’t just dirt……it was lice! We were so used to having lice, I didn’t even realise how bad it was. The officers came and asked us: “who needs hospital?” Not one of us said yes- all I thought of was Dr. Mengle. But they came again and assured us that there wouldn’t even be a German nurse! Its all British! The army. Do not worry. So, I went.

The first month was hazy, I don’t know. But I got better. They took me out of bed. I asked the staff, what happened to me? What was wrong? They said, you had a killer disease- typhus. I’d never heard of it. After about three months a nurse came to me and said, soon you will be able to leave. I said good – where am I going to go? She said- there’s a camp near here, I will take you. I said no way, I’m not going to a camp. She explained it was run by the British army- no guards, no fences, and I’d be free. I asked here- what will I wear? They burnt my clothes! She told me she already had an English boyfriend, so a few days later she comes back….with a British army uniform! She altered it for me, but she made me promise that upon arrival in the camp I should dye the uniform. I promised her I would. When my friends saw me in the uniform, they couldn’t believe it! They asked me, when will you dye it? And I said- never! I will never dye that uniform! I will keep it and wear it. The military police kept stopping me, I was fifteen but I looked younger. But they didn’t speak Polish. So, someone had to translate to explain why I was wearing it.

Journey to England

Hannah: How did you end up coming to England?

Zigi: When we were liberated, the reason I’m in England…We went to a camp, and then we went to a children’s home. Then, we heard that there are homes in England and Sweden that are allowing children under sixteen. They asked me, do you want to go to England, and I said no! To me, England felt like a few thousand miles away. So, where do you want to go? They asked. So, I said, Palestine…I’d be able to speak the language. Of course, at the time, I didn’t realise that I couldn’t speak the language, I spoke Yiddish- but not Hebrew or Arabic. They said, if you want to go to Palestine then alright, but there’s a quota there, and not many people go a month. I said, I’ll wait.

After a while, they took us to Hamburg which was nearer to the boats to Palestine, and we were staying in the most beautiful place outside Hamburg. It was given by a Jewish family before the war, so we all stayed there waiting, quite a few hundred of us.

Unfortunately, I did something which I shouldn’t have done, and I hurt myself, you know? I had to go to hospital and stayed there for two weeks. Some friends of mine came to pick me up and they brought me a letter from London, England. I thought to myself, who would write me from London, England? So, I opened the letter, its written by a woman in Polish and she said, she used to be in Poland in the city of Łódź, and she had seen a boy with the same name as her son on a cross-list in London. The only problem was, the date of his birth was incorrect, so she asked me to take a look at my left wrist. As a two-year-old child, after my parents had divorced and my mother left when I was about three years old, I had a mark and she said it is possible that you still have the mark. When she asked me this, we’re talking about 1945…so I had a look and there it was. [Zigi shows me a small mark on his left wrist].

So, as I read on, she said if you are my son, then I want you to come to London. I looked at my two friends and said “there’s no way I’m going”. She might be my mother, but I don’t know who she is! Anyone could say it. When I went back to where we were staying, where we were being looked after by the British and American army and the Jewish Brigade, they went mad with me! The said, How can you not go?! You found a mother, look at your friends…they’ve got nobody. So that’s how it was.

I first arrived at England on a boat via Hull. A man met me, turns out it was my stepfather. He took me to the west end of London and I met my mother. We cuddled and we cried. But the first six months were hell for me. Everything I wanted; they did for me- within two weeks I had two suits.

Did you explain to your mum what you had experienced during the war?

Oh, she already knew. So, I stayed with her, and it was terrible for me. They did everything for me, but I missed my family. My family were those boys who saved my life- from the camps. One day I was walking in the street with a friend and he said you know those kids who came here in 1945, who lived in Windermere in the Lake District, they are finished there. They went to Glasgow, to Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool but most are in London. They have a place in too called the Primrose Club, and every once a week there was a dance there, and girls came too. Some born in the UK, some were survivors, the majority were Jewish.

So, I went there one day, knocked on the door. The first thing I said was – at last, I found my family again. About twenty percent, I knew. With “The Boys” – we talked about our experiences amongst ourselves, but not with anyone else or with strangers. I became very involved with the club. We did trips together, it was wonderful. And, they are my family up until today, though I am one of the last left. My life completely changed, I was working as a tailor which I hated, I had a girlfriend- she came in 1939 with her family. She is now my wife of sixty-five years! We opened a shop together, a delicatessen on Finchley Road. But it was hard work, it wasn’t Kosher and there were a lot of Germans in the area. So, I began to work with my father-in-law, selling stationary. Eventually we built a printing press, and I worked there for a long time. We had children, so I asked to become a partner. But it didn’t happen, so I decided to carry on my own accounts. So, I started working for myself, and earned some big accounts. I started working with Save the Children, supplying to them. We opened a couple of shops too, and in 2002 I retired.

I could never thank the British for what they have done for me. I am so lucky to alive, and my children and grandchildren. My children and grandchildren are all interested in the Holocaust, and have worked with the Holocaust educational Trust. They go to Auschwitz; they write a lot. I was asked to speak in Westham Football Club, close to where my granddaughter lives. Maybe you saw it in the press, it was after there had been some antisemitic chanting at one of the matches. It was shown on television. But overall – I can’t tell you what a wonderful life I’ve had. I can’t believe I have lived to this age!

Life After the War

Hannah: Once you began talking about your experiences, and going to do tours of Auschwitz, did it help you to deal with the tragedy?

Zigi: Speaking about it makes me feel much better. Once I told somebody about it, it helped. Especially young people- the most important people in the world They are our future. And you know, every year schools do a Holocaust Memorial Day- this started small, and every year it gets bigger and bigger. The reason is, the third generation knows more about the Holocaust than the second generation. We didn’t talk so much about it to our children, you know. They got to know because of our friends all being survivors, but we tried to live our lives and we were busy. Who wanted to talk about it?!

It is interesting, the story of how I got started talking publicly with the Holocaust Educational Trust. I delivered stationary to a client in Westminster, on the second floor at the offices of Jewish friends of Israel. Once, I was coming down the stairs the door was open to the HET offices. I had a look inside, and the girls were working. So, I went to ask- maybe I can supply them too! They said yes etc, so I said what do you do? They said – we are Holocaust educational Trust, we take people to Auschwitz. And I started laughing! They asked me why, and I said because I am a Holocaust survivor. I first went back to Auschwitz, thirty years ago. Nothing beat me as much as the room with the toys of children, shoes, suitcases….it just got to me.

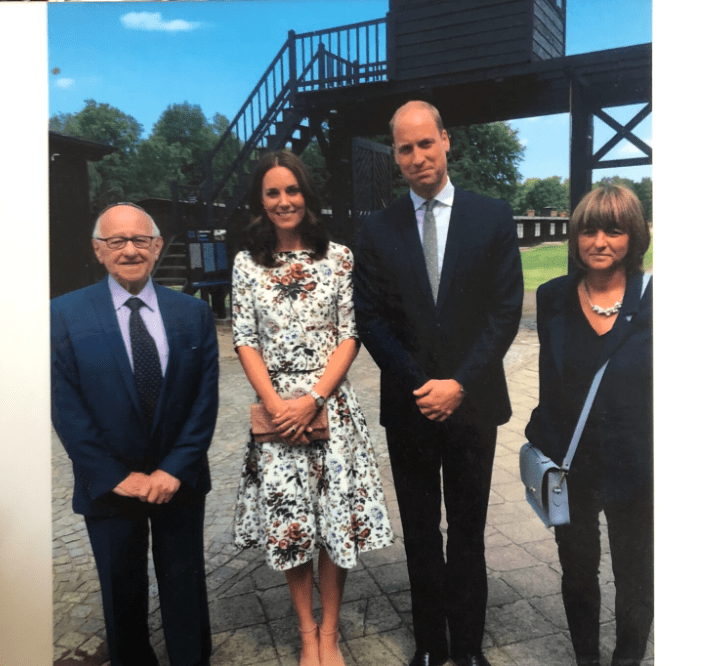

You know, in 2017 I was invited to go to Stutthof with Prince William and the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton, along with another survivor too. I took my daughter; she took lots of photos. You can see how miserable they look, but they were lovely. They cried and read a prayer. We laid memorial stones together. It was a very meaningful experience.

Hannah: That’s wonderful, Zigi. Can you give any words of advice for the BAHS, our members and readers, as researchers of the Holocaust?

Zigi: Oh yes- and everyone who knows me well knows this. When they say to me, do you hate Germany? And I tell them no, why would I? How could I? Why would I hate you because your grandparents committed a crime? Why should I hate you? We are no better or worse than anyone else. Do not hate, hate is the worst thing that can happen to you. You’ll hate everyone, including yourself, and you it will ruin your life. And never, ever give up! Even if you fail, if you want to get there – if you want to, you will. It might be harder for some than others, but don’t give up.

And I always try to make my audiences laugh. When people ask me why, I saw – will being miserable bring back my family, who were slaughtered for no reason? No. Why shouldn’t I be happy? Whatever Hitler tried to do, I’ve got six grandchildren, two daughters, three great grandchildren. Why shouldn’t I enjoy life? And I do enjoy life, I always did. From the minute I was reunited with the Boys at the Primrose Jewish Club, I enjoyed life.

This article is dedicated to the memory of the millions of victims of Nazi Persecution, and to the family of Zigi Shipper.