by Peter Davies

Peter Davies is Professor of Modern German Studies at the University of Edinburgh, UK. His current research focusses on the role of interpreters and translators at post-Holocaust trials in Germany, and on the transmission and transformation of testimonies through reformulation, remediation and translation. He has published on the intersection of Holocaust Studies, Memory Studies and Translating and Interpreting Studies. Recent publications include: Interpreting at the First Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial: How is a Witness heard? (Bloomsbury, 2025), Witness between Languages: The Translation of Holocaust Testimony in Context (Camden House, 2018), and with Hannah Holtschneider, Sheila E Jelen and Christoph Thonfeld, Olga Lengyel, Auschwitz Survivor: Interdisciplinary Explorations (Palgrave MacMillan, 2025).

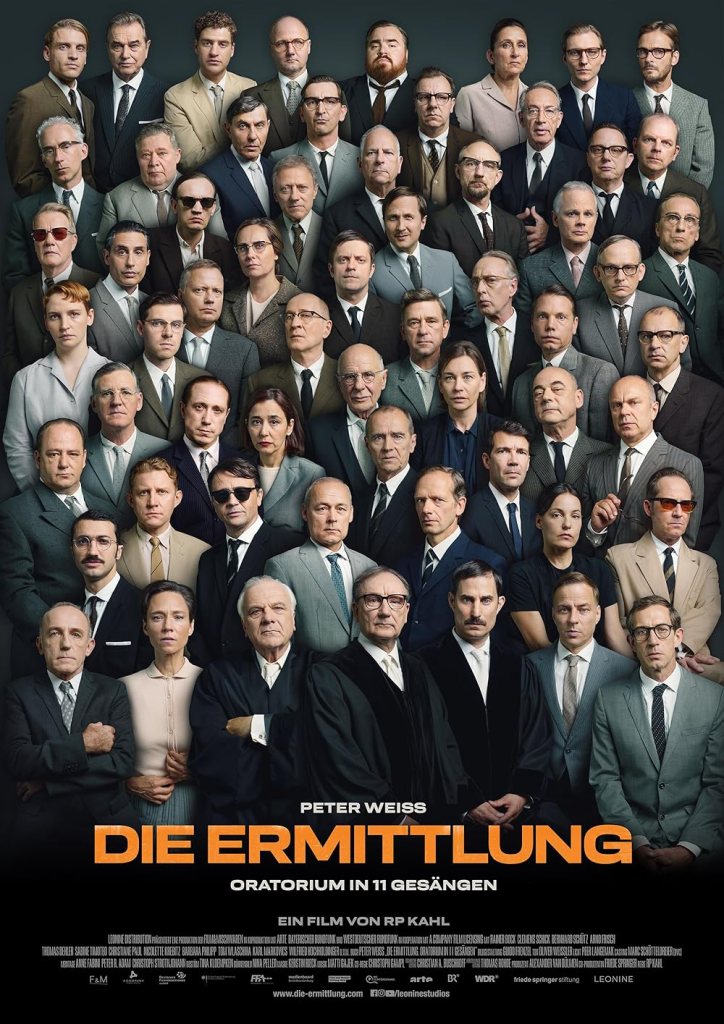

A new film version of Die Ermittlung is a big deal (dir. RP Kahl, 2024). It is clearly prestigious and well resourced, with a huge cast – far more than any theatre production could hope to work with – and with some well-known actors.[1] I saw it in Berlin, in the beautifully intimate Kino Central in the Hackesche Höfe, with 8-10 others scattered through a 100-seat theatre. I’ve taught Peter Weiss’s text for many years to different groups of students, and so a new film version is always going to give me new ideas, though it does mean I respond to it in a different way to other viewers. Knowing the text well means that there is less of a shock effect on encountering the narratives and conflicts for the first time: it would be interesting to know whether any viewers of the film come to it now without having at least read the play. I thought it would be useful to write this on one viewing of the film, to see what I took from it; all I have done afterwards is look up the cast.

The new film works with a large space, suggesting a tv studio, sound stage or large studio theatre. The defendants ranged in the background on a stand are almost always visible behind the witnesses when they approach the microphone in the centre of the space. The judge, played by Rainer Bock, sits facing the rest of the room, and (as far as I remember) we are never shown the space from behind him, except for the occasional high angle shot when a witness walks away from us to leave: so the edges of the space are clearly defined and we, through the camera, are inevitably inside it. The witnesses enter and leave the performance space, and on occasion, the accused are shown taking a break between scenes (Weiss’s Gesänge, or ‘cantos’), walking off chatting as a group and coming back in.

Banks of lights are also visible at the sides of the space, and are often present in the shot. This arrangement allows for variety in creating angles and striking images, establishing relationships and conflicts between individuals, and creating subtle distinctions in the presentation of each canto through lighting, framing and camera angles. We see reactions from all participants, either in the background in interaction with what is being said or in cutaways to individual reaction shots. This loosens up the dramaturgy of this long film, though the reactions are often hard to read, and are not simple expression of emotions: we are never told what to feel through actors’ expressions.

The scenes are introduced not by film material, but by the overhead aerial reconnaissance photos taken by the Allied air forces, with the buildings and spaces highlighted that are spoken about in the scene. This feature pulls us out of the theatre space and positions us as observers from on high, raising questions about knowledge, complicity and (non-)intervention and making a connection with passages in the text in which witnesses talk of their hopes that the camp complex will be bombed.

It felt – and this is a subjective judgement based on one watch – as if the actors have been given significant leeway in individualising both accused and witnesses through intonation and gesture. It is absolutely not the case that the play is free of emotion: this view of the play is the same attitude that misreads Brechtian dramaturgy as ‘emotionless’. The play is about ways of speaking and not speaking; it is not about the expression of emotion, but about what emotion means. The witnesses’ speech is still very controlled, and the emotional outbursts of the accused are shown to be manipulative. Weiss does not allow us to believe in the convenient short cut that emotional authenticity is a foundation of truth: truth must be relentlessly uncovered and questioned, rather than being expressed or revealed.

There is, however, a specific emotional dramaturgy in this production that I found very striking. Weiss’s text is structured as a relentless progression to the final canto, from arrival at the camp to the gas chamber, but the production has found a different, emotional, arc that intensifies somewhere in the middle of the film through close ups and lighting effects, rather than at the end. A devastating moment in the central portion of the film is the account by a female witness of her own sterilisation and torture during ‘experiments’ on female prisoners. This is always an unbearable moment, even when reading the play, and the text shows her making the courageous decision to speak about an experience that she has tried unsuccessfully to put behind her. In Weiss’s text, she speaks about this long silence, but in the film, the actress (Sabine Timoteo) makes an excruciatingly long pause and hesitates in her words: we are shown her face, tense with repressed rage and pain, and some reactions from other participants. There are no other such pauses in the film, though other actors sometimes show tiny hesitations before speaking, so this silence stays in the room throughout the rest of the film.

Weiss’s view was that Auschwitz can, and must, be talked about clearly and directly: silence in this play is not about the supposed impossibility of representation (which Weiss regarded as a mystification) but about physical and emotional damage, injury to human dignity and the courage to speak. The accused are part of a world in which speech is easy – they chat casually to each other and to the defense council and can count on their words being understood in the world beyond the court – whereas the witnesses need to be relentless in their precise expression to cut through the barrier to understanding.

I mentioned that the cast is enormous. There are a couple of interventions in Weiss’s text that produce very different effects to the original intention, and which I think are positive. The original text introduces nine witnesses, two of them female – the only female voices in a play that mostly negotiates forms of masculine behaviour in perpetration and resistance – and two of whom are not survivors, but former SS men or other individuals complicit in the system who have been called in evidence. The film’s cast is multiplied by the decision to divide Weiss’s witnesses into more identifiable individuals: the cast list for the film gives 39. The figures in Weiss’s text are composites, stitched together from different sources in the trial transcripts and characterised in subtly different ways that do not directly correspond to the personality of an identifiable individual trial witness. The witnesses in the film are individualised, with more female witnesses than Weiss envisaged, and the long monologues are sometimes cut into exchanges where two or more witnesses stand together.

These thoughts lead to an interesting question raised by Weiss’s play, namely its treatment of the survivors’ language use. The courtroom exchanges in the First Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial (1963-65), which form the basis of Weiss’s text, were multilingual, with witnesses speaking eleven different languages and both witnesses and accused speaking many regional varieties of German, as well as many more or less fluent non-native speakers who gave testimony in German: it is a treasure trove of linguistic behaviours, translation and hybridising, and highly individual modes of testifying. The process of courtroom interpreting into German, transcription of the courtroom exchanges by Hermann Langbein and others, and Weiss’s procedure of excerpting, cutting together and rewriting led to a purely Hochdeutsch script. Weiss’s text (and all the other German productions I’ve seen) are effectively a Lehrstück performed by and for Germans who have to occupy the positions of both accused and witness in order to test their reactions and emotions and to critique processes of identification. To put it critically, Weiss’s text suggests that the Holocaust is a German concern.

The film does something radical with the witnesses, which may not come through in the English subtitles. Not only does it make them more individual and break up Weiss’s composite figures, but also employs some actors whose first language is not German, speaking with a range of accents. This transforms the impression made by the text: it not only provides some variety in diction and personality, but more importantly makes clear through the voices the international scale of the Holocaust and of the survivor community, showing that Holocaust memory can’t simply be a matter for German internal consumption (I’m reminded, from a different angle, of recent discussions about the stake of non-majority culture Germans in public memory of the Holocaust). I hadn’t expected this when I went in: the film takes a gently critical attitude to Weiss’s text, retrieving a sense of the original witnesses’ voices and nudging at contemporary debates.

[1] A subtitled trailer is available here [viewed 11.2.2025]. At time of writing, the film is available in Germany on the ARD Mediathek, on Arte, and on DVD.