Dr Daniela Ozacky Stern

Over the last hundred years, the city of Kobryn has known four different regimes: Polish, Soviet, German, and Belarussian. The upheavals of the twentieth century left their mark on its residents, mainly on its thriving Jewish community, which no longer exists.

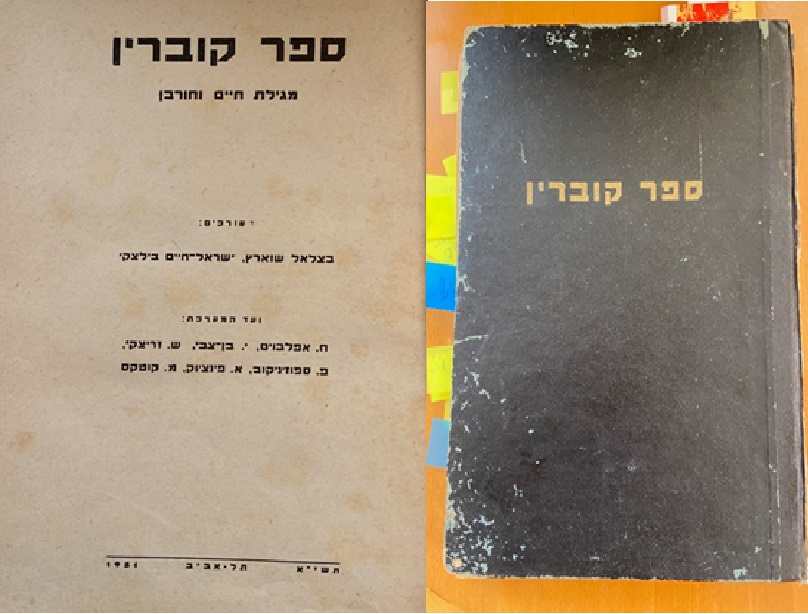

In 1951, a small group of Jewish survivors issued a modest Yizkor [memorial] Book in Israel, which included historical surveys of their hometown, old photographs, and eyewitness testimonies and reminiscences of those who survived.[i]

The Yizkor Book of Kobryn

Kobryn is my paternal grandfather’s birthplace, but I never had a chance to hear his story since he died years before I was born. As it turns out, my father, who was born in a Displaced persons camp in Germany after the war, had little knowledge about his family’s background. They, like many others, did not talk with their children about the Holocaust since they wished to raise them ‘normally.’ He knew only that he was called after his grandfather Yud’l (Yehuda), who perished in the early stage of the war.

As much as I nagged my grandma and aunt, my father’s older sister, they refused to discuss the past. It took me two trips to Kobryn, a thorough reading of the Yizkor Book, and other resources to learn about my family’s fate. Along the way, a long-hidden family secret was exposed in the most peculiar circumstances.

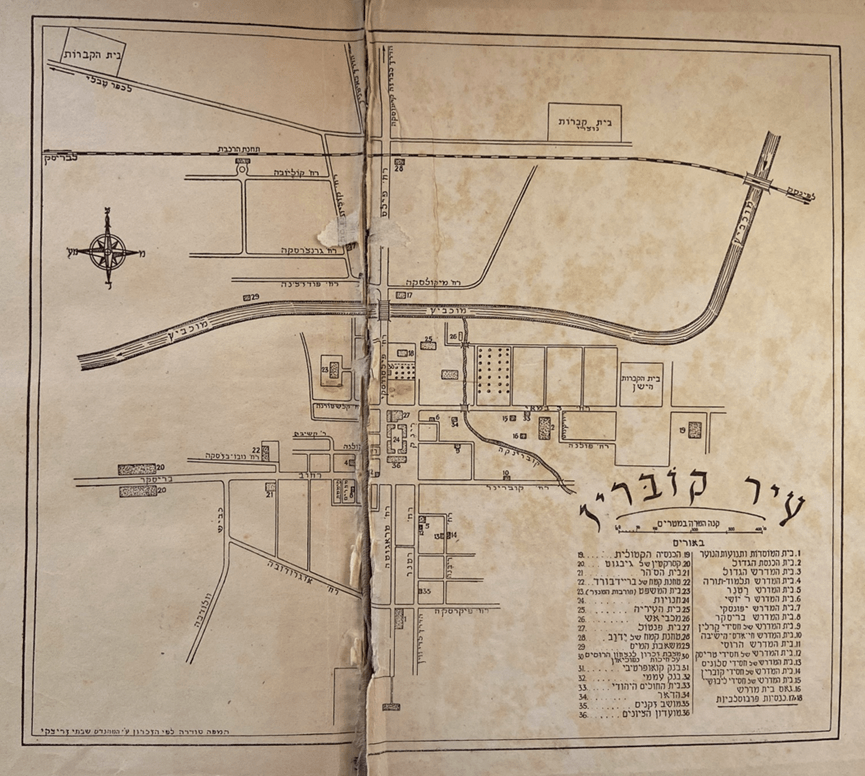

About 6,500 Jews lived in Polish Kobryn on the eve of the Second World War. Like most Jewish communities, it was well organized and had autonomous institutions, schools, religious and cultural life, differences in economic status, and political divisions. No less than sixteen midrash places for studying the Torah were open to all, and the grand synagogue was the throbbing heart of the community life. Several smaller Shtetls were scattered around Kobryn, and they used their services to boost the country’s economy. The region’s central city was Brest, an important border town known for its castle, a junction of roads and transportation, and the famous site of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty of 1918, where the borders of the Soviet Union had been established.

Several entries in the Yizkor Book vividly and nostalgically describe daily life in the town, illustrating the marketplace, the riverbank with its wooden bridge, and many more small details of their “vanished reality.”[ii] When the Balfour Declaration was announced in November 1917, a big ceremony was held in the synagogue where Rabbi Levitas called upon his people to donate as much as they could for “Building a safe home in our desolate country.”[iii]After a short hesitation, a respected woman named Zis’l got on the bima (a raised platform in Jewish synagogues) and started taking off her jewelry, including her wedding ring. In the next hour, many followed suits, and a large pile of gold watches and expensive jewels was collected.[iv] A party was held when they learned about the establishment of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in April 1925.

“Kobryn did not excel in its wealth; no industry nor big commerce existed there, and its people found their living in petty trade and shopkeeping.” Many young people left for Eretz Israel, and other destinations, and their parents planned to follow them.[v] The main Jewish neighborhood surrounded Pinsker Street, stretching from the city center down to the Mukhavets River, which had become the first death site of the Jewish men right after the German invasion of 1941. Most buildings on the street were of two stories, the ground one for a shop or a small business and the second for the family residence.

The Ozacky family men were shoemakers. In their workshop on the first floor, they made rubber boots for farmers in the area. On Fridays, they closed the shop early, moved the machines, and cleaned the room to set a big table for the Shabbat family meal. In addition, they kept some cows and helped take their neighbors’ cattle to graze by the river. They were not involved in politics nor tended to Zionism, so when the earth started shaking under their feet in the early 1930s, two brothers and one sister immigrated to the new world. Since they did not get visas to the US, they ended up in Cuba. Not long after their arrival, they set up a shoe-making factory, this time making sandals for the ladies and leather boots for the army. Life was good for them until Castro’s revolution in 1959.

When the Soviets entered Kobryn in mid-September 1939, following the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact,[vi] Shmuel Ozacky, my grandfather, the only son who stayed in town, joined, or was forcibly recruited, to the Red Army, and thus his life was saved.

Ghettos and Holocaust by Bullets

In June 1941, Nazi Germany surprised the Russians and the world by attacking Soviet territories, breaching the pact they had signed less than two years before. Kobryn was occupied, and its Jewish population was immediately subject to violation, burning of homes, and murder. Yud’l Ozacky was one of the first victims of the “Holocaust by bullets” of Kobryn’s Jewish population. He hid under a bridge for a few days but was discovered, tortured, and shot at, in what had become the first death site of the town. It was July 1941. From then on, this was the method of killing in the murder operations against the Jews, which came in various scales. A month later, the second Aktion targeted sick and infirm Jews, all killed by bullets.

Two ghettos were formed in November: ghetto A, with about 600 skilled professionals who would work for the German war industry, and the larger ghetto B, where all the rest of the Jews, including about 2,000 from nearby small towns, were held, mostly the elderly, women, children, and others who were “not useful.” The ghettos in Kobryn did not last long; hundreds of people had been shot sporadically over the next months until the final blow came. The third mass murder was in July 1942, when ghetto B was liquidated, including the hospital with its workers and patients. All of them were cruelly murdered by shootings in Bronna Góra[vii] shot into lime pits, with many others collected from nearby towns. The final mass murder in Kobryn happened in the Autumn of 1942 with the liquidation of ghetto A. An eyewitness who escaped the ghetto miraculously wrote a report in real-time in Polish in which he documented in detail what happened on October 13-14. This was translated into Hebrew for the Yizkor Book and provides a unique testimony of the last days of the ghetto in Kobryn.[viii]

It was twilight of a hot day when he and a group of inmates dragged their feet, walking back to the ghetto after a long working day led by a tall German. “I was very tired but could not sleep. How can one sleep calmly when the scenes of the last months in the ghetto are reflected in front of one’s eyes…?”[ix] He dozed briefly, startled by a noise from outside and a big commotion inside. It was 3:30 a.m., and the streets were busy with people running around, confused and helpless. Suddenly, the ghetto gate was opened, and the Germans entered “deadly skulls painted on their caps, rifles and pistols in their hands, shouting wildly: everyone! get out!” At that moment, he thought: “I wish we were organized if only we had arms to rise and not fall into their hands like shreds. We could have killed some of the murderers so their blood would soak this cursed earth. But it did not happen…” His family had prepared a bunker, so they managed to hide for three days, all the time listening to the cars go back and forth, and the non-stop screams, wondering if this was the end of the ghetto. They were discovered and chased out, walking in the destroyed streets while the Germans were still searching every house for more hiding Jews. Bill describes tangibly the torture, humiliation, beating, and shooting along this horrid journey, mentioning names of people he recognized and not sparing harsh details. In an instant, he jumped over a fence and started running fast, not thinking, hiding in a sewage pit, in a cowshed, in a tunnel. “The stubborn wish to live ordered me to run forward… I moved only by instinct.”[x] This story had a good ending. He managed to pass to the Aryan side, hid by a kind Christian woman who knew his sister. After a while, he paid someone to take him to Warsaw, changed his name, disguised himself as a Polish citizen, and lived with a local family until 1947. He later returned to his true identity as Gedalia, left Poland, and after a few years in Argentina and the US, came to Israel with his wife and four children and lived happily till his passing in 1990.[xi]

Resistance

After the mass murder in Bronna Góra, an underground of about eighty youngsters organized to escape to the forests and join the partisans; unfortunately, they were not successful. Most of them were murdered by local farmers before arriving at their destination. The short time between the Aktionen and the fast liquidation of the ghettos did not allow enough time for another underground to emerge. However, there were personal performances of bravery and resistance, with or without weapons. A young partisan named Gershon Tenenbaum happened to be in ghetto A when the massacre occurred. He fought a group of Germans in the street, and when he ran out of bullets, they shot him to death. A female teacher dragged his body and buried him in her garden. A young woman, Rachel Goldin, managed to steal a few hand grenades from the German workshop she worked at and attacked them when the Aktion started. As an act of revenge, they did not shoot her but beat her to death in front of the people in the street. Two young fellows set fire to the deserted houses in the ghetto and were shot to death. The physician, Dr Chaim Goldberg, shot the Germans who came to take him and saved the last bullet to shoot himself, thus not falling into their hands. Two other doctors, Milner and Liberman, refused to extradite their families to the murderers and poisoned them.[xii]

Bill, who witnessed part of these events, wrote that many Jews resisted bare-handed and desperately struggled with anything they could get until their last minutes. Aharon Herman, who survived and made it to Warsaw, wrote a letter in May 1946 telling about the last days of the ghetto and mentioned names of more individuals who resisted, like Mot’l Bereznik,[xiii] who stood alone to enter the train car and took a rifle from a Germans and killed several Nazis, until they slaughtered him; Abrasha and Hannah Herman stood at their home entrance blocking it from the Germans and attacked them with a German hand-grenade he took from one of them and killed ten Germans before he was shot.[xiv] Those “small” resistance acts became a legacy of Kobryn.

The estimated number of escapees from the ghettos was around 500, but local Polish and Ukrainian peasants handed over many of them to the Germans. About one hundred survivors of Kobryn ghettos had made it to the partisan forests, but at the time, there was chaos and a lack of arms, and soon, the Germans hunted the partisans, and many of them were killed. All in all, about one hundred Jews survived in Kobryn, and a few came back from the USSR.

Commemoration

Almost one-third of the Yizkor Book is devoted to short monographs on central dignitaries of the community – rabbis, teachers, public figures, artists, doctors, and more. Only two women are mentioned among the dozens of male personages. Both were teachers and did not survive.[xv] This unique primary source enables us to draw a partial sociological portrait of an average Jewish community in the periphery of Poland before the war. Though incomplete, it sheds light on the social elite and who was considered part of it.

Rabbi Michael established an only religious-national school named Tvuna [wisdom] that had become an important cultural institute; Dr. Yosef Priwolski was a communal physician who served the entire population and was elected to the city’s council, becoming a deputy of the mayor in the 1930s; Elias M. Grossman started his artistic career drawing local Kobryn characters whom he met in the streets, but had grown to be a world-renowned painter, who traveled the globe and painted Mussolini, Bialik, Mahatma Gandi and others; Engineer Abraham Levitas started his Zionist activities at age twenty, was a skilled orator and the community’s representative to the 12th Zionist Congress. He later established the first Tarbut [culture] school[xvi] in Kobryn and became its headmaster; Rabbi Moshe of Kobryn was the last of the well-known Hassidic dynasty of the city who perished with most of his followers.

The list is long and demonstrates that the most appreciated fields in the Jewish communities were rabbinate and education. True, there were affluent merchants, wealthy dealers, and professionals in many productive crafts. Still, when the time came to commemorate the town, its survivors chose to demonstrate its humanistic figures and show pride in their religious and educational leaders.

What Remained?

“Is it fate’s irony or a bitter joke of history?” asked Shmuel Segal in his short contribution to the Yizkor Book. The truth is that what remained of Kobryn, a vivid town of Jewish life, is only a book.[xvii] And how could a book express the essence of Kobryn? He asks himself. “It would be just a pale reflection of life flowing so strongly, of the struggle of ideas and opinions… is it fair and appropriate even to try to articulate in writing what is impossible to be expressed?” And yet, he found some solace in the fact that the book would provide the descendants of the scattered remnants of Kobryn’s natives and survivors a picture of the rich Jewish life and the history of their hundreds of years of struggle to maintain their culture, institutions, and community life despite persecution and pogroms. Indeed, reading through this book and other Yizkor books of communities that perished gives the next generations (and the historians) not just dry information on dates, events, and facts. It opens a wide window to bring in the atmosphere, the spirit, the emotions, and the sights. It helps us imagine the daily life of our ancestors, how the town and the market, the synagogue, and the school looked like, how the people related to each other, and how they lived. One can feel the poverty and agony, side by side with the joy and achievements, the solidarity and warmth despite political divisions and disputes. Not all is bright and well, of course, but the nostalgia and longings pop from every page. In short, a Yizkor Book may seem gray and dull from the outside, but once you dwell in it – you find a treasure.

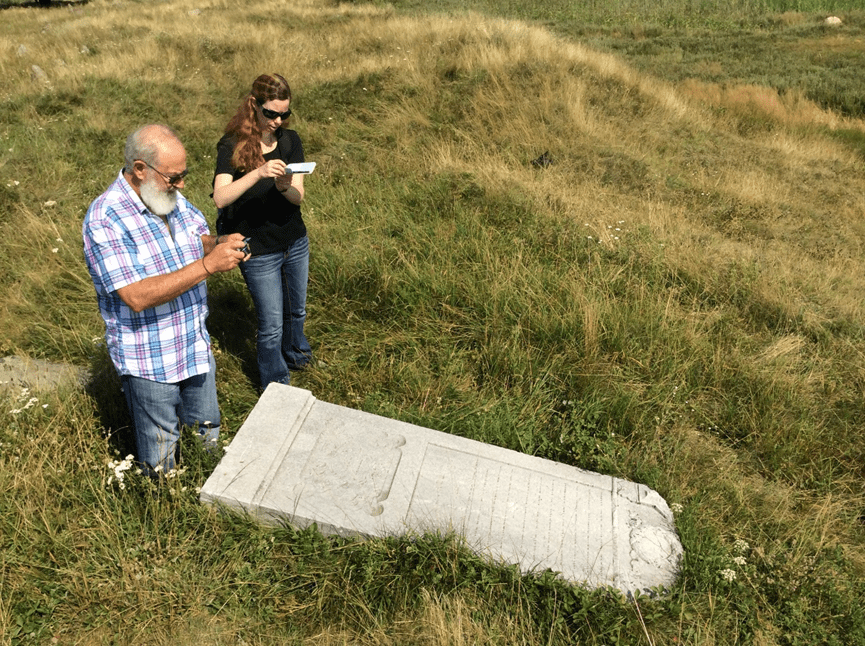

Kobryn today is a typical average Belarussian city of approximately 60,000 residents. There are still monuments of Lenin and Stalin and several others of past heroes and special events. The Second World War, “The Great Patriotic War,” is present, naturally commemorated by statues, signs, and names of streets. As is common in the former Soviet countries, there is hardly any specific mention of the ethnic or national belongings of the “victims of Fascism” on the big monuments. However, at the place of the final mass killing of the city’s Jews in October 1942, I found a board of marble with a Hebrew inscription reading: “Here are buried 4,500 Jews, citizens of Kobryn, who were murdered and destructed by the Nazi German Fascists [a Hebrew date]. May their memory be blessed.” A smaller sign in Hebrew was erected on the former site of the old Jewish cemetery, and there are some smaller monuments of this kind.

A remarkable Jewish remnant of material culture stands in Kobryn. This is the high building of the great synagogue, which dates back to the 18th century. Even though empty, desolate, and neglected, it is still an impressive edifice built of red brick stones that rises above its surroundings. Plans to renovate it have been made, but as far as I am aware, they have not been fulfilled yet. Jewish Kobryn no longer exists, but it’s ghosts hover above its sky.

Epilogue: A Family Secret is Exposed

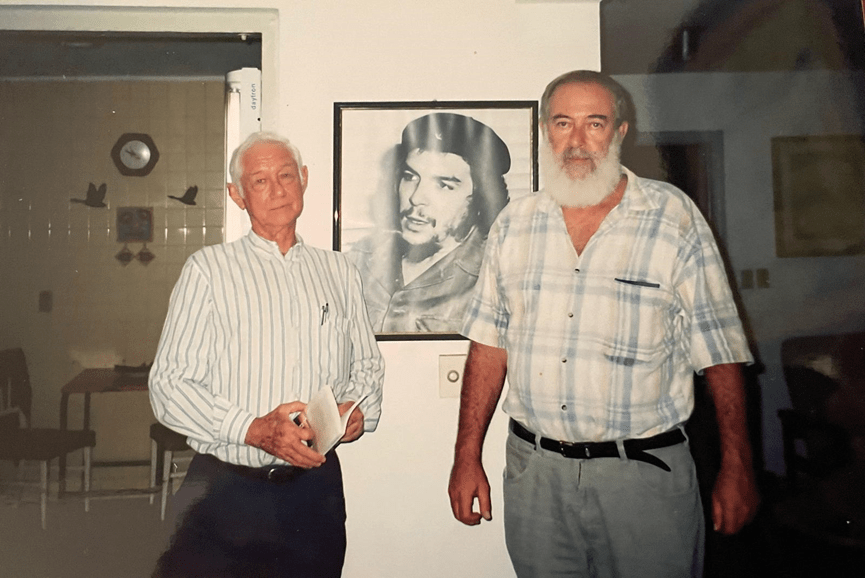

In 2004, my father went back to Cuba, more than forty years after being smuggled out to Israel as a fourteen-year-old child, in fear of recruitment to the revolutionary militia. Only one member of the Ozacky family stayed on the island after Castro’s revolution. My father’s cousin Enrique Oltuski-Ozaki[xviii] joined Fidel Castro and Che Guevara on the journey to power as the treasurer of the underground and was very close to them. When they established their government, he was rewarded with a high position as a communication minister, the youngest and the only Jew in the revolution.[xix] The meeting with my father was emotional, and at one point, Enrique started reminiscing about their mutual grandfather, Yud’l. The light went off, as it usually does in Havana, and he took a small flashlight and read in Spanish a chapter from his other autobiographic book about his childhood.[xx] It was the story of Yud’l’s murder, as he learned from his mother. “He was hiding under the bridge with his baby granddaughter. On the third day, she started crying of hunger and cold, and the Germans discovered them. Both were murdered after a long torture.” Yud’l was forced to walk naked in the streets and dig his own grave. Wait, my mother said, who was the baby? All his children had left Kobryn. Whose baby was it? Enrique looked at my parents with his blue eyes and said: She was the daughter of your father Shmuel, your sister.

My parents were startled, having heard that Shmuel had a wife and a daughter before the war and that both were murdered when he was in the front with the Red Army fighting the Germans. What was her name? he did not know, nor did he have any data on who was her mother. When Shmuel returned to Kobryn after the war and found no one alive, he sealed his lips and started a new life. He later took his new family to Cuba, where his brothers had settled, and never spoke about the past.

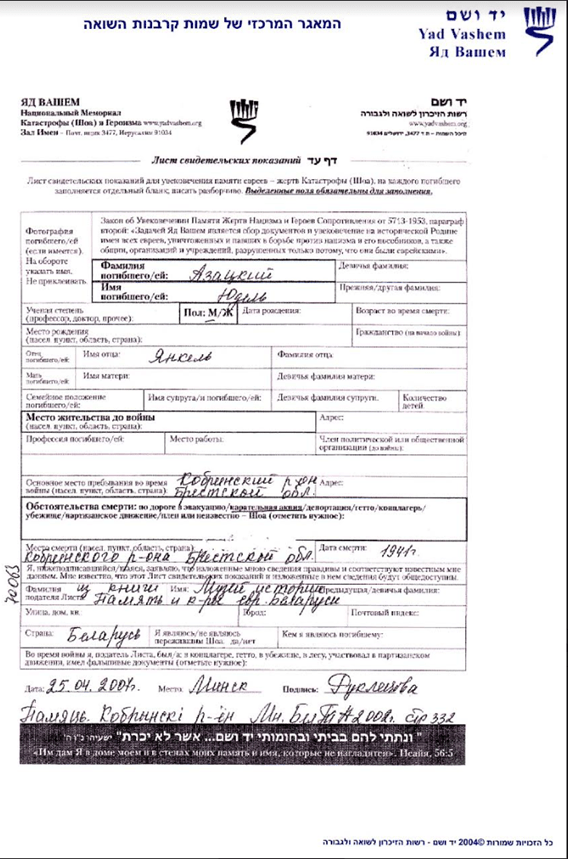

I traveled with my father and brother to Kobryn in 2014. We consulted the nice ladies at the information center on how we could find data on our family. She recommended a book in the Belarussian language. It was a thick memorial book published in 2002 by the municipality, memorizing the city’s history from the Middle Ages to the present. On page 332, they helped us find the name of Yud’l Ya’akobovitz Ozacky in a list of Jews murdered at the beginning of the occupation in 1941.

No mention of other family members was to be found. The baby and her mother remained anonymous.

[i] An English version of the book was published forty years later: Betzalel Shwartz and Israel Chaim Biltzki (eds.), The Book of Kobrin: The Scroll of Life and Destruction, translated from Hebrew by Nilli Avidan and Avner Perry (San Francisco, CA: Holocaust Center of Northern California 1992).

[ii] See, for example, Chaim Appelbaum, “The Vanished Reality,” 185 and Israel Chaim Biliztki “In my City’s Paths,” 165, in the Kobryn Yizkor Book (Tel Aviv, 1951).

[iii] Efraim Polonski, “Notes on my town,” 71.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid, 69.

[vi] The city was occupied by the Germans in September 1939 after a three-day battle with the Polish army. In November, it was transferred to the Soviets as agreed upon during the pact.

[vii] A mass killing site 30 kilometers east of Kobryn, where more than 50,000 Jews and non-Jews were murdered.

[viii] Yizkor Book, 319-331.

[ix] G. Bill, “The Holocaust,” Yizkor Book, 326.

[x] Ibid, 329.

[xi] Interview with Gedalja-George Bill, https://sztetl.org.pl/de/stadte/k/948-kobryn/104-texte-und-interviews/196210-polish-roots-israel-george-gedalja-bill-about-his-life-and-family-kobryn

[xii] Yizkor Book, 329-330.

[xiii] Ibid, 330.

[xiv] Ibid, 332.

[xv] Ibid, 211-299.

[xvi] A renowned network of Zionist-Secular-Hebrew schools in East Europe operated between the two world wars and reached 270 schools in 1939.

[xvii] Yizkor Book, 198.

[xviii] That’s how he spelled his family name. His original first name was Zvi Hersh.

[xix] His autobiographical book on his life in the underground was translated into English: Vida Clandestina, My Life in the Cuban Revolution (San Francisco: Wiley, 2002).

[xx] Enrique Oltuski, Pescando Recuerdos [Fishing for Memories] (La Habana, Cuba: Casa Editoria Abril, 2004).