By Dr Imogen Dalziel

2024 marks 30 years since the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, when at least 800,000 people were murdered in 100 days – sometimes by their own neighbours, friends or family. This year’s British and Irish Association for Holocaust Studies Conference at the University of Exeter featured a keynote from Dr James Smith, co-founder of the National Holocaust Centre and Museum and founder of the Aegis Trust, on ‘Holocaust Memory, Rwanda, and Genocide Prevention Today’. Continuing this commemorative theme, in this month’s blog post, BIAHS Professional and independent historian Dr Imogen Dalziel reflects on her visit to Rwanda in the summer of 2023, witnessing the receipt of charitable donations and considering the ongoing impact of the genocide.

Please note: this post contains descriptions which some readers may find upsetting.

Two things made an immediate impression on me when our group arrived in Rwanda. The first was the friendliness of the people, which continued throughout our visit. Most people greeted us warmly, with a huge smile and handshake, exclaiming, “You are very welcome here in Rwanda!” Even those who were initially slightly shyer would place a hand on my arm as they spoke, or envelop me in a grateful hug when they had received their gifts or donations. I enjoyed being referred to as a “sister” amongst the younger generation; although this term of endearment comes from a Christian perspective of community, I was often made to feel like a long-lost family member who had been expected for some time.

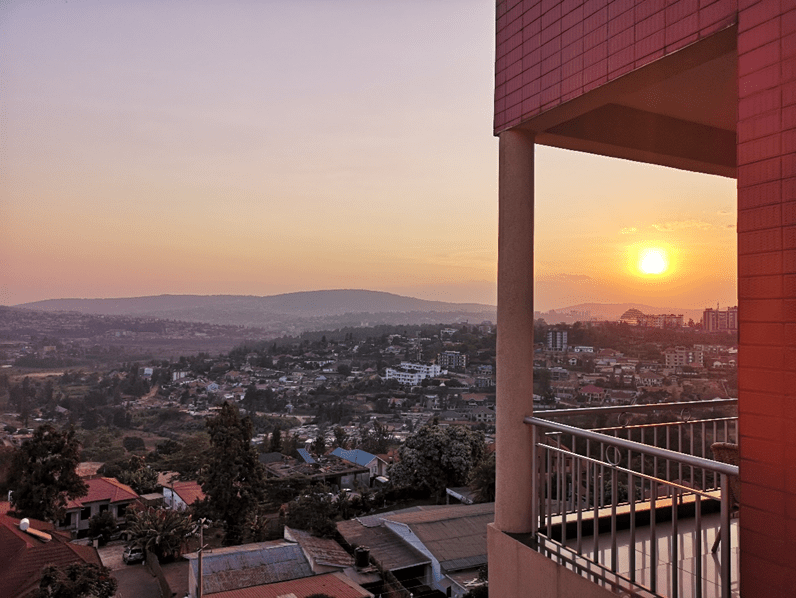

The second was the beauty of the landscape. Rwanda is known as ‘the land of a thousand hills’ for a reason; the greenery of the undulating slopes, peppered by clusters of one-storey houses and falling away into rivers, banana plantations and national parks, was a welcome change of scenery. The weather was warm, but not oppressively so, and the colourful skies of the sunset were truly spectacular. My time in Rwanda unfortunately did not allow for an excursion to see the gorillas or the ‘big five’ on safari, so I can only imagine what such an experience would have added.

But this was not the case 30 years ago. After decades of ethnic division, anti-Tutsi propaganda and outbreaks of violence, in April 1994 Rwanda erupted into genocide after Hutu President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down upon its descent into the capital, Kigali. The Tutsi minority, as well as some moderate Hutus and Twa, were massacred by armed Hutu militias, often killed with machetes or clubs. Moreover, thousands of Tutsi women were kidnapped and kept as sex slaves, many contracting HIV and/or giving birth to children born of rape. Those same streets, hills and rivers were littered with bodies. People took refuge in the national parks, risking the danger of encountering wild animals rather than the perpetrators.

This dichotomy stayed with me for the duration of my week-long visit with Survivors Fund (SURF), a wonderful charity that operates both in Rwanda and the UK to help genocide survivors and their families. Our itinerary primarily comprised three aspects: charitable activities; an introduction to Rwandan culture; and visiting memorial sites.

Charitable Projects in Action

The main focus of our charitable activity was at Philly’s Place, a free children’s education centre established by SURF in Bugesera. Some children walk as much as 10km each way – often in threadbare shoes and ill-fitting clothing – for lessons. During our visits, we ran arts and crafts sessions, face painting and a games afternoon. Each time, word of our arrival quickly spread, and we were soon overwhelmed by dozens of hands reaching out for materials or sports equipment! On our final day, we brought a dozen suitcases, each filled to the brim with toiletries, children’s clothing and shoes that had been generously donated in the UK. Seeing the delight on children’s faces upon receiving a new pair of shoes, T-shirt or toothbrush will stay with me for a long time. A purpose-built Philly’s Place is currently under construction to accommodate more children, and will open within the next year.

We also visited Rwanda’s only centre for elderly genocide survivors, whose families were wiped out in 1994. After hosting a raffle with donated presents, we played a few games and were then all treated to a performance of traditional Rwandan music and dance.

In a small village west of Kigali, our group participated in redecorating houses that had recently been rebuilt for survivors and their families. The local children arrived in droves to see what we were up to – and I soon found myself holding the hands of our affectionate onlookers instead of a paint roller! In this village (and another), we also presented residents with goats and cows, sponsored by ourselves and/or friends and family. The milk and meat produced not only provides food for the recipients; they can be sold to generate some desperately needed income.

One of the highlights of my visit was meeting Laetitia, a 29-year-old born of rape after the genocide. She and her mother, who suffers from severe mental health issues, live in cramped quarters with other relatives. Laetitia wished to start a small business selling charcoal, earning enough money to eventually obtain somewhere to live with her mother. Bolstered by donations from colleagues, family and friends, I was able to tell her (via translation into Kinyarwanda) that she now had the money to establish her business, and that I would continue to support her once I returned home. It was an incredibly emotional moment, and I am pleased to say that I am still receiving updates from Laetitia, who has made a very promising start in her venture.

Imigongo and Umuganda

I have read and heard much about the genocide in Rwanda, but knew very little of the country’s culture before we arrived. Several times, our group watched performances of both contemporary and traditional Rwandan dance, particularly the Intore (a pre-colonial war dance). We attended workshops in African drumming, weaving and Imigongo, painting wooden boards decorated with geometric shapes fashioned from dried cow dung. I was also surprised to learn there is a Muslim Quarter in Kigali; we were guided around its beautiful architecture, colourful street art and the ever-popular milk bars. On one afternoon, we were taken to the labyrinthine Kimironko Market, haggling for clothing, bedding, cooking equipment and non-perishable foods for the families we were visiting. The smells, sounds and piles of goods were a stark contrast to the quiet, minimalistic interior of the Kigali Heights shopping centre, where we bought ice cream after our long day of painting and decorating.

Finally, a few of us elected to get up early on Saturday morning and take part in Umuganda, compulsory community service that takes place from 08:00-11:00 on every last Saturday of the month. The local leader was delighted to have us, and we spent an hour threshing weeds along the roadside, before each being invited to plant a bamboo tree. We – very originally – named each tree after ourselves!

Commemorating the Genocide

Aside from our charitable activities – and, perhaps, as the staunchest reminder of why they were needed – we visited three different genocide memorials. On our first day in Rwanda, we were given a guided tour of the Kigali Genocide Memorial, close to the city centre. The building’s permanent exhibition explains the history of the colonisation of Rwanda and the events before, during and after the 100 days of killing. We were also shown a section dedicated to murdered children. Square, silver plaques in front of photographs of beaming toddlers and schoolchildren stated their name, some facts about them (such as their favourite food or best friend) – and then how they were killed. This memorial in particular brought me to tears, and provided greater emotional context to a ceremony in which we laid flowers on one of the mass graves around the site, where around 250,000 victims are laid to rest.

At Ntamara Genocide Memorial Centre, a former church where at least 5,000 Tutsis were massacred, we were joined at another ceremony by a genocide survivor who now works with SURF. It was the first time he had returned, and the pain and emotion in his eyes were clear. Understandably, he did not accompany us for the tour, in which we viewed the clothing, personal possessions and skeletal remains of those who had sheltered in a place they deemed safe.

Our final commemorative visit was to the Nyanza Genocide Memorial. Those seeking refuge at the nearby École Technique Officielle – portrayed in the film Shooting Dogs – were marched to this former rubbish dump and murdered in their thousands. Across the road from the mass graves is the beautiful Garden of Memory including many symbolic elements, some of which were inspired by Jewish and/or Holocaust memorials. A large stone in the shape of Rwanda, for example, sits atop a plinth, while hundreds of thousands of small rocks, paying tribute to the victims, lie under 100 stones representing the 100 days of genocide. Additionally, a small pond, hedges and ridges symbolise the lakes, bushes and hilltops where the persecuted either hid, resisted, or were murdered. I was struck by the tranquillity of the garden, particularly when contrasted with the busy, noisy road below. It served as a reminder of how, whilst the mass murder of Jews in the Holocaust primarily took place in forests and concentration camps in rural areas, the genocide against the Tutsi unfolded right in the heart of the urban landscape.

This comparison is greatly illustrative of my personal experience of visiting these memorials. Initially, I considered them from an ‘academic’ perspective, thinking about the various similarities and differences with Holocaust museums and exhibitions. Emotional engagement, however, quickly took precedence. One cannot fail to be moved by viewing the piles of human remains on display. The flag-draped coffins in underground crypts. The bloodstains still visible on a wall of Ntamara’s former Sunday school, where children were murdered. And, after seeing such things, observing the quiet grace of those who survived, raising their families and working to ensure that their children will never be subjected to the horrors they experienced 30 years ago.

There is so much more I could write about my time in Rwanda. Certain aspects were not seen or discussed, such as the government’s political repression against their opponents, even those who have fled the country. (As one expert told me before my visit, this is certainly not a conversation starter – you never know who might be listening. A scene in the recent ‘Rwanda’ episode of The Misadventures of Romesh Ranganathan highlights this perfectly.) Until recently, there was also controversy surrounding the former Conservative government’s plans to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda, and the treatment they may have received upon arrival. The knowledge that we helped individuals or local communities improve their education, livelihoods or housing, however, if only in a small way, is what has remained with me since I arrived home.

Rwandans still live with the physical and mental scars of 1994, never far from a mass grave or former killing site. But the warmth, generosity and gratitude of the people we met was inspiring, and left me desperate to one day return to the land of a thousand hills.

For more information on the Survivors Fund, or to make a donation, please visit the Survivors Fund website.