by Charlie Knight

Charlie Knight is a Postgraduate Researcher at the Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton. He is funded by the Wolfson Postgraduate Scholarship in the Humanities for his research into German-Jewish refugees from Nazism in Britain. He was the joint postgraduate representative for the British and Irish Association for Holocaust Studies in the 2021/22 academic year, and currently teaches German History at the School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies at UCL.

‘Does tolerance still define Britain today?’

This important and especially poignant question was asked by Clare Fraenkel at the end of her humbling and thought provoking new play I was a German. Blending conversations of the past, present, and future, one cannot help but see Fraenkel’s question as rhetorical – a self-evident assertion of falsity. In recent weeks Holocaust survivor and educator Joan Salter MBE went viral for speaking out against the language of hate used by those in power, fuelling the intolerance of those in British society who would wish others harm: “When I hear the kind of rhetoric being used by our politicians against desperate refugees trying to make their way to safety here because they see the UK as a welcoming place for them to settle and bring up their children, I am concerned […]“.

*

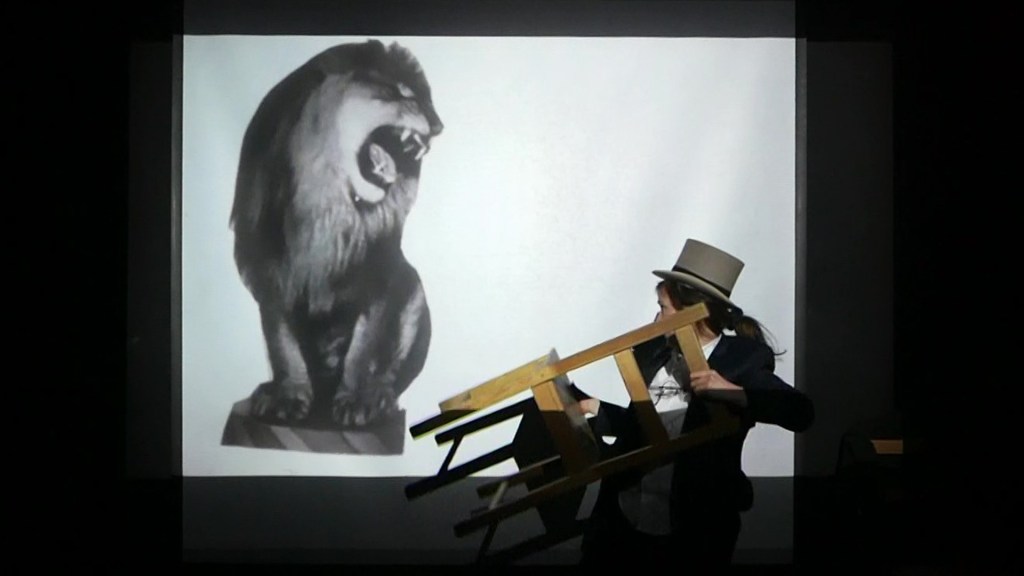

Through the work of its writer/performer Clare Fraenkel, I was a German examines a multitude of interlocking concerns temporally and generationally split and yet informing on each other constantly. The play, with showings at Camden People’s Theatre, JW3, and most recently London’s VAULT Festival, tells the simultaneous story of the playwright’s process of regaining her German citizenship post-Brexit, alongside the story of her grandfather, Heinrich Fraenkel, from his escape from Berlin in 1933, to the end of the 1940s and the Berlin airlift. Aided by the beautiful lighting, shadows and projections by Shadowboxer Theatre, and music by Arran Glass, Fraenkel creates an interactive and yet immersive space to learn, provoke, and consider questions of nationality and belonging. Clare Fraenkel’s grandfather Heinrich ‘Heinz’ Fraenkel was born into a German-Jewish family in Lissa (previously German, now Polish) in 1897, although moved to Berlin at a young age. He went on to become an advertisement representative and writer for several big Hollywood firms for central Europe, and later a journalist for The New Statesman. As Clare Fraenkel tells it in I was a German, Heinz was at a film party in Berlin showing the latest picture starring Austrian Jewish actress Elisabeth Bergner, when he decided to leave. Whilst there he was warned by a ‘friendly Nazi’ (a remark quickly followed by the quip ‘I don’t know what that means’) that the Gestapo were at his house waiting for him and that he must flee. Heinz finished the party first and boarded the night train to Paris, before ending up in England without his clothes or belongings.

By 1940 Heinz was interned on the Isle of Man in Hutchinson Camp, recently the topic of a mass study by Simon Parkin in his work The Island of Extraordinary Captives. Fraenkel (and Parkin) tackles the anxiety and mental health struggles felt by many Jewish refugees in Hutchinson faced with the prospect of invasion in the summer of 1940, albeit briefly. Parkin writes that Heinz was ‘willing to endure internment, but not invasion’ and kept a razor blade with him always, a prop comedically used by Fraenkel at other points in the piece to represent the overbearing moustaches of the British establishment. Whilst in Hutchinson, Heinz contributed to the artistic cultural life of the camp through posing chess problems, something he later did for The New Statesman under the pseudonym ‘Assiac’, beautifully represented through one of Fraenkel’s numerous suitcases on stage opening up to reveal oversized chess pieces. Heinz had managed to navigate his new existence through publishing anti-Nazi works through his friend Victor Gollancz and even went on to co-found the Free German Movement. After proving his tolerance interviewing Nazis party members post-war, Heinz returned to Germany as a correspondent for the British media although quickly realised that this Germany was not what he had once known.

Recently in an event run by the Association for Jewish Refugees, the Wiener Holocaust Library, and the German Embassy, comedians Matt Lucas and David Baddiel discussed the process and implications of regaining German Citizenship, previously taken from their descendants. In an earlier piece for the Jewish Chronicle, Baddiel wrote:

“But of course, there is an issue beyond the bureaucratic. My grandparents, Oti and Ersnt Fabian, were very German — my grandfather, for example, insisted to his dying day that Goethe was better than Shakespeare — but both of them, deeply damaged by their experience, refused ever to go back to that country, or have much to do with it at all. My mother too, although claiming to be able to speak the language — she couldn’t, my mother was always saying things like that — had similar antipathies. I don’t.“

Fraenkel’s I was a German reaches into these questions and asks if German citizenship is something for her to take when her grandfather chose not to return. Her questioning over the applicability of ‘The ‘Eleventh Decree to the Law on the Citizenship of the Reich 25 November 1941 restoration of citizenship under Article 116 (2) of the Basic Law (Section 15 of the Nationality Act)’ (often a point of joviality in the piece for its bureaucratic sound) garners the question how her grandfather would have felt. Indeed the title is emblematic of Ernst Toller’s book of the same name written in 1934. Toller questions his German-Jewishness and his place in this new society below, something Fraenkel presents perfectly stating this country called ‘Jewish Germany’ no longer exists and therefore questions where she is gaining her citizenship back to: “Is blood to be the only test? Does nothing else count at all? I was born and brought up in Germany; I had breathed the air of Germany and its spirit had moulded mine; as a German writer I had helped to preserve the purity of the German language. How much of me was German, how much Jewish? I could not have said. […] The words, “I am proud to be German” or “I am proud to be a Jew,” sounded ineffably stupid to me. As well say, “I am proud to have brown eyes.”

Fraenkel’s play is a complex and yet accessible depiction of the life and times of one man’s existence in an era categorised by un-belonging. In playing both herself and her grandfather, Fraenkel converges time in a way that brings the facts of the past into stark contrast with the present. Whilst the focus on the Berlin airlift at the end feels slightly out of place, it is clear that Fraenkel understands the importance of her grandfather’s story and the narrative of the thousands of other refugee tales that are gradually becoming more known. As family collections emerge from the attic in dusty suitcases, one cannot help but admire Fraenkel’s attempt to share the difficult aspects of an often sanitised refugee past with members of the general public in the present. Her script and performance, alongside the brilliant direction of Lowri James, provide the audience with an opportunity to ponder Britishness and the values that supposedly entails. As Fraenkel opts to give the last word of the show to her grandfather, this review will afford Heinz the same opportunity, but will do so asking whether his words truthfully transcend the past, present and future:

“My decision to make my home in England [was important], for this is the land where some tolerance is for ever being practised and the tacit respect for other people’s opinions […] both the land of my birth and the land of my choice would do well to take a leaf out of each other’s book; and to copy a bit of the one nation’s gluttony for work and the other’s sense of tolerance“.

For upcoming performance dates please click here.

Sources:

Joan Salter, ‘I confronted Suella Braverman because as a Holocaust survivor I know what words of hate can do’, The Guardian Opinions, 17th January 2023, Accessed via: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jan/17/confronted-suella-braverman-holocaust-survivor-refugees-home-secretary,

Simon Parkin, The Island of Extraordinary Captives (London: Sceptre, 2022)

David Baddiel, ‘I’m half-German. But is going full German a step too far for me?’, The Jewish Chronicle, 9th September 2021, Accessed via: https://www.thejc.com/lets-talk/all/i’m-half-german-but-is-going-full-german-a-step-too-far-for-me-1.520280

Ernst Toller, I Was a German: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary (New York: Paragon, 1934)

Heinrich Fraenkel, Farewell to Germany (London: Bernhard Hanison, 1959)