by Mark Wilson

Mark Wilson is a PhD History candidate at Durham University. His research explores experiences and meanings of place and emotion in oral histories of the Holocaust in France.

(‘Seeing Auschwitz’ is a co-production of Musealia and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, and runs until the end of January 2023 in South Kensington, London)

It is hard to miss ‘Seeing Auschwitz’. The entire ground-floor façade of the exhibition venue displays full-length panels with images from Auschwitz, confronting passers-by in the street outside, urging the public to engage and reconsider how we ‘see’ Auschwitz as the abiding symbol of the Nazi genocide.

The main aims of the exhibition are pedagogical. Its key mission is to provide visitors “with the tools to reflect for themselves on the reality of Auschwitz and the Holocaust”. Arguably, ‘Seeing Auschwitz’ achieves what is sets out to do in this regard: this is a well-curated collection of photos, artwork and other visual sources that has a lot to offer to scholars and to the general public.

A strength of the exhibition is how it deconstructs images produced by the Nazis themselves. The viewer is encouraged to recognise how these are not “neutral images”. Photographs taken of new arrivals at Auschwitz, of victims disembarking from trains and being prepared for selection, are blown up to cover entire walls of the exhibition. The text accompanying the images, and the excellent audio guide, draw attention to details that humanise the victims and urge visitors to “choose to view critically and with compassion for the individuals depicted.”

Alongside the sensitive critique of these perpetrator images, we also see Auschwitz from the victim perspective. Although fewer in number, the photographs and artwork produced by victims are incredibly powerful. This includes the photographs taken and smuggled out of the camp by members of the Sonderkommando, and the sketches by a prisoner, identified only by the initials ‘MM’, which were hidden in a bottle in one of the prisoner barracks. These images convey Auschwitz as seen by its victims: the brutality and terror, as well as scenes of resistance that do not feature in any of the Nazi visual records.

The stories behind the images reveal the precarity and contingency of our visual record of violence and genocide. They also tell us important things about the victims, of their agency and determination to document and communicate Nazi crimes to the world beyond Auschwitz. Nearly 39,000 of the ‘Auschwitz mugshots’ were saved by Wilhelm Brasse, a political prisoner who had taken many of the photographs. Helped by his comrade Bronisław Jureczek, Brasse blocked the air outlet to extinguish the fire in the stove and defy the SS who had ordered him to burn the prisoner mugshots.

An attentiveness to the experience and artefacts left behind by victims offers new ways of seeing Auschwitz. The exhibition displays twelve of approximately 2,400 surviving photographs – of social gatherings, weddings and births – that were among the personal belongings of the victims. These photographs are shown alongside images from the Karl Höcker album, depicting the camp staff at leisure in the nearby resort of Solahütte. ‘The World That Was Lost’ images sit between enlarged photos of an SS choir of guards and camp administrative staff and, on the other side, three SS men and a group of female Helferinnen who run laughing across a bridge towards the camera.

Self-portrait of an unknown woman. Title image of ‘The World That Was Lost’ section of the exhibition.

One of the pre-war photographs prompts us to stop and reflect more deeply on this juxtaposition. Captioned ‘Self-portrait of an unknown woman’ the image depicts a young woman in a round-necked cotton dress. She is poised, taking a photograph of herself in a mirror with the camera propped up on a book which she holds carefully in place as she takes the picture. She is looking down in concentration. The image hints at the inner world and creativity of this young woman, a self-awareness that her persecutors seemingly lack. We cannot know her exact fate but we are reminded as we contemplate this photograph of the fullness of the lives taken at Auschwitz.

The exhibition perhaps underplays the importance of oral history as a ‘partner’ to the visual sources. In some parts of the exhibition, images work powerfully in conjunction with other types of sources, especially oral histories. Applying this approach more broadly across the exhibition would be a promising way of helping the viewer to understand the events and experiences depicted. The section of the exhibition that presents ‘The Sonderkommando Photographs’ combines photographs and artwork with excerpts of oral history interviews from surviving members. Together these make for a compelling account of the complexities of the Sonderkommando.

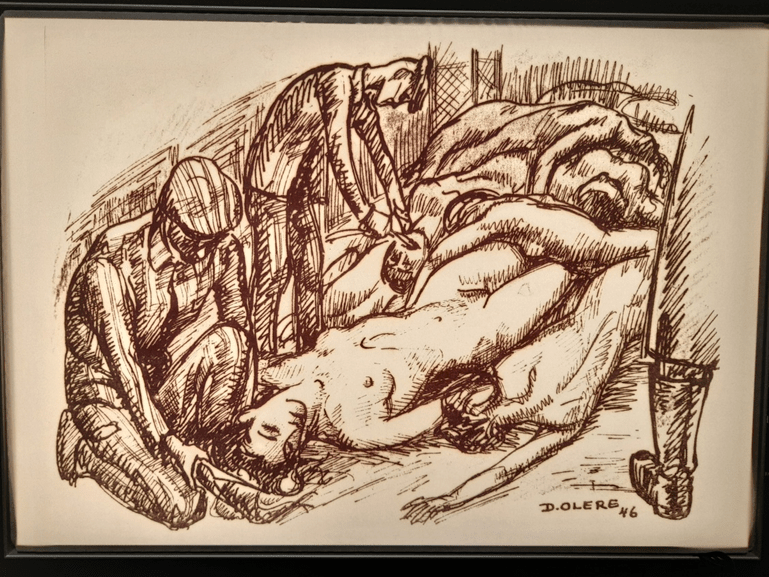

A sketch from 1946 by David Olère: the ‘dentist’ and the ‘barber’.

But the images alone also convey some of this complexity. One of the sketches by David Olère, a surviving member of the Sonderkommando, reproduces the brutal environment of the gas chambers and the ambivalence of the Sonderkommando’s participation in the process of murder and disposal of the victims.

Under the watch of an SS guard, two members of the Sonderkommando attend to the dead in a gas chamber. The ‘dentist’ and the ‘barber’ are shown removing gold teeth and cutting hair from the victims. We do not see their eyes or the detail of their faces. The corpses are similarly indistinct, except for the body of a young woman whose naked form is centred in the foreground of the image. Her eyes are closed and face seemingly peaceful as the ‘barber’ gently starts to cut her long, dark hair.

The men are solemn, with heads bowed as they work. Are they concentrating on their tasks? Intimidated by the guard’s presence? Or do we see here the shame felt by a former member of the Sonderkommando whose acts, however coerced, made them complicit in an unbearably intimate and gruesome way, in murder and the desecration of the victims’ bodies? It is a difficult, haunting image.

Many of the images exhibited here are familiar from textbooks, documentaries or fictional representations. Photographs from the liberation of Auschwitz evoke our sympathy and pity at the sight of skeletal survivors in three-tiered bunks. Other images connect us with the murdered victims in different ways. In one such photograph, taken after the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz in 1945, investigators are shown discovering piles of human hair.

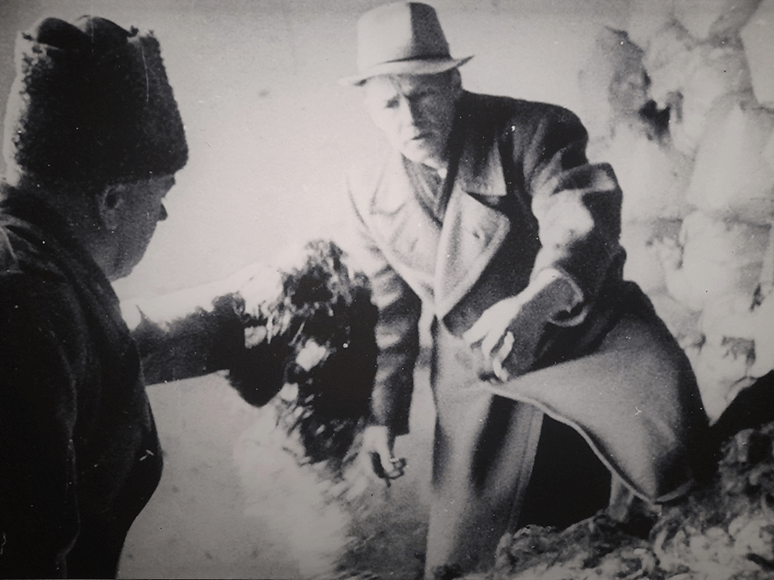

Soviet investigators inspect bags of human hair (1945).

This image, depicting the moment in which the man facing the camera reaches out to touch a handful of hair with a puzzled frown on his face, connects viewer and subject in their attempt to grasp the scale of the crimes and lives taken. The caption tells us that seven tons of women’s hair – cut from the heads of 140,000 people – were discovered at Auschwitz. While separated by time and space, we look on at his discovery and feel the same sense of quiet horror and disbelief. Like him, we start to really see Auschwitz in the vastness of its inhumanity.

Images of Auschwitz beyond the exhibition

As part of the approach to engaging the public beyond the exhibition itself, the audio guide encourages visitors to select three images to share on social media, using the hashtag #SeeingAuschwitz. This is encouraged further by the exhibition’s official Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts.

‘Seeing Auschwitz’ sets out a clear case for the power of the visual image in helping us try to understand Auschwitz. It is a compelling and sensitively presented exhibition which prompts important questions. One – perhaps unintended – question relates to how we should handle images of victims. The ethical treatment of photographs that show victims of the Holocaust was raised in a thought-provoking paper at the July 2022 BIAHS conference from Chloe Smith: ‘Orphan Images: The Significance of the Absence of Consent and Holocaust Atrocity Photographs’. Here, there is perhaps a less critical approach taken to encouraging the sharing of images on social media by visitors.

Screenshot from the ‘Seeing Auschwitz’ official Twitter account.

Certainly, for the most part those posting on social media about the exhibition reflect on the images with sensitivity. However, others express discomfort with using atrocity images of victims and choose instead to post only photos from the exhibition that do not show victims. And there is a strong feeling of dissonance when considering some Instagram posts in which images from the exhibition share space with selfies and food pics, and where #SeeingAuschwitz is used alongside other hashtags such as #weekendvibes, #londonlife and #happyday.

Within the exhibition space itself, the sensitive curation of these images is beyond reproach. Without detracting from the exhibition overall, we are nonetheless reminded that there is still much for us to think about regarding how we use images to evoke and discuss the Holocaust more broadly.

Thanks to Cécile Guigui (Queen Mary University London) and Sophie Dubillot (Open University) for their comments on a draft of this review