by Daniel Adamson

Daniel Adamson recently submitted a PhD on British Holocaust education at Durham University. He now works as a teacher of History and Politics.

‘What would I have done?’. This is a question many of us will have asked ourselves in relation to the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Few of us would like to think that we would have been active participants in genocide. Yet, as Edmund Burke’s much-quoted aphorism reminds us, ‘the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing’. C.P. Taylor’s play Good (written in 1981) throws this moral dilemma into sharp focus. The new production directed by Dominic Cooke at the Harold Pinter Theatre offers a pessimistic outlook on the ability of humans – even those who consider themselves ‘good’ people – to comply with the worst of society.

Good follows the transition of John Halder (played by David Tennant), a professor of literature based in Frankfurt, from ambivalent spectator to the Nazi regime to a fully-fledged participant in some of its most heinous crimes. Over the span of eight years, Halder becomes increasingly seduced by the appeals of the fascist state, leading to a spiralling involvement in the mass censorship of ‘degenerate’ culture and the burgeoning euthanasia programmes. This staging is a discursive three-hander, with the supporting cast of Elliot Levey and Sharon Small flitting skilfully between characters ranging from Halder’s senile mother to, at one point, Adolf Eichmann. Through Halder’s conversations with his peers, we witness the troubling detachment of the man from his morals. Timestamps of key historical events – the book burnings of 1933, the Night of the Long Knives (1934), the November pogroms (1938) – all act as staging posts of Halder’s desensitisation to the horrors unfolding throughout Germany.

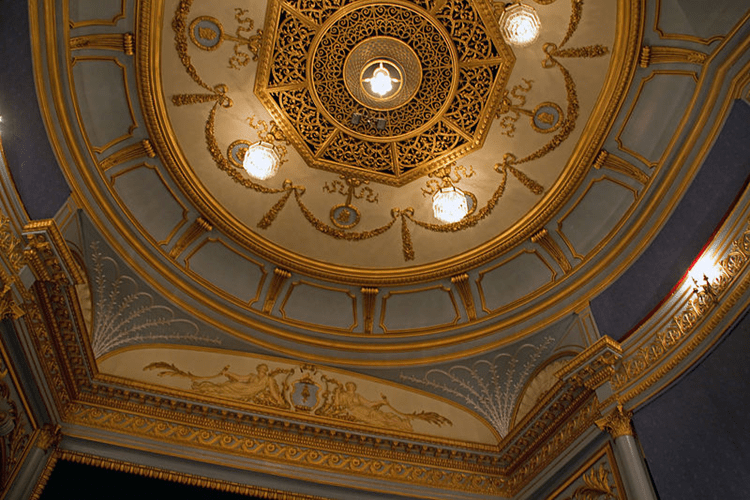

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harold_Pinter_Theatre_Ceiling_(8280921097).jpg

One particularly striking dimension of the Harold Pinter theatre’s production is its use of immersive audio-visual experience. So often, modern audiences experience the history of Nazi Germany through a detached prism. Black-and-white photographs can only convey what life was really ‘like’ to a certain extent. But Good affords its audience a sense of the whole picture. In one distressing scene, a violent wall of sound envelopes the theatre as Jewish homes and businesses are destroyed during the Night of Broken Glass. A stark reminder, if needed, that these events were lived experiences, not simply lines in historical textbooks. In many ways this staging mirrors the process of Gleichschaltung, whereby Hitler’s government established a creeping totalitarianism that engulfed the totality of German life. Evidently, the production has benefited from the work of the BIAHS’ own Dr Caroline Sharples (University of Roehampton) as historical consultant.

All the while, the bunker-esque aesthetic of the set reinforces a sense of claustrophobia, as each character becomes increasingly cornered by the social and individual realities of the situation. Within the confines of the Spartan stage design, Halder must come to recant on his initial comment that antisemitism is ‘just a balloon they [the Nazis] throw up in the air to distract the masses’, especially as life for his Jewish friend Maurice (Elliot Levey) becomes impossible. As Halder becomes trapped in his own convictions, the selfish human instinct to survive emerges as the key driver which leads ‘good’ people to do ‘bad’ things. This transition is most evident in Halder’s costume, which evolves with troubling speed from a non-descript tweed suit to the menacing black uniform of the SS officer corps.

In a historiographical sense, Good offers plenty of food for thought. Halder’s gradual realisation of policies towards the deportation and extermination of Jews subscribes to the school of thought that many German civilians had a rough knowledge of the skeleton structures of the Holocaust, if not its precise details. Usefully, Taylor’s play also blurs the boundaries of rigid categorisation. Rather than casting each character as a ‘victim’ or a ‘perpetrator’, there is a more nuanced approach than this simple binary approach. Halder’s character embodies the hazy moral landscape of the period, as a man who considers himself to be ‘good’ becomes entangled in the unspeakable. Taylor places emphasis on the individual motivations of each person involved in the crimes of the Nazi state. These were people motivated not necessarily by psychopathic predilection, but rather the self-serving benefits of complicity with the regime.

Good depicts the grim realities of Nazi persecution. But there are surrealist elements too. Halder, portrayed with a sinister erudition by Tennant, has a tendency to fantasise about music spanning Bavarian brass bands to Wagnerian operas. An unexpected, and at times jaunty, soundtrack thus accompanies the base horrors which unfurl on stage. Yet this never feels inappropriate. In the cold light of hindsight, Good reminds us that there is a sort of absurdism – in the philosophical sense – about what happened in Nazi Germany. How did the world allow this to happen? We perhaps too often take for granted the depths to which humanity sank under the aegis of a supposedly rational society.

Undoubtedly, Good is a challenging watch, but one which feels essential. Although rooted in the history of Nazi Germany, it has universal appeal as a meditation on human nature. It is to the credit of this production that the moral quandaries of the play linger in the memory long after leaving the theatre. There is no choice but to reflect: how would I have acted in a society in which the choice between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ seemed so obvious, but in reality was so complex? Above all, Good is a poignant reminder that the Nazi regime and its associated atrocities were human constructs: their agents and victims were real people. This is a play, therefore, which gives us a harrowing insight into one aspect of what Hannah Arendt christened ‘the banality of evil’.

Good runs at the Harold Pinter Theatre in London until 24 December.