Charlie Knight, Hannah Wilson and Natali Beige

Charlie Knight is a PhD candidate at the Parkes Institute, University of Southampton, funded by the Wolfson Foundation, his research focuses on German Jewish Refugees in Britain and their connections to families left behind. He previously completed his MA at the University of Exeter and is now one of two BAHS Postgraduate Representatives for the 2021/22 academic year. He has held research placements with the National Trust but has most notably volunteered volunteered with the IWM Holocaust Galleries Research Team.

Hannah Wilson is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Public History, Heritage and Memory at Nottingham Trent University, where she currently works as a research assistant. She has received funding awards from Midlands4cities and the La Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah for her ongoing research into the material memory of Sobibór. She is a Web, Blog & Social Media Coordinator for British Association for Holocaust Studies, and an MA graduate of the Weiss-Livnat International MA program in Holocaust Studies at the University of Haifa. She has also participated in the archaeological research at Sobibór and Treblinka death camps. Hannah was also a placement content researcher at the IWM Holocaust Galleries for over a year during their development.

Opened to the general public on the 20th October 2021, Imperial War Museum’s new Holocaust and Second World War Galleries marks the first time two connected galleries on these topics are housed under one roof. The curators of the Holocaust galleries have created a space that is honest, emotional and different – a better representation of the current trends in Holocaust scholarship, and a more wide ranging approach the the genocide without ever loosing sight of the personal stories at its heart. The team of the SWW galleries have equally created a truly global exhibition drawing on personal stories from all sides of the conflict, moving away from a Eurocentric narrative to one that represents all who fought and died.

Aiming to depict the interconnectedness between the Holocaust and the War whilst still maintaining their separation and specificity, the galleries intersect at the imposing tilt of the V-1 Doodlebug bomb previously displayed in the main atrium of the museum. As a key part of the European war narrative, the doodlebug also represents many thousands of lives lost through slave labour at camps like Mittelbau-Dora where it was created. From the SWW galleries you look up to see the V-1 cascading towards you and from the other side you see the bomb moving away, with blue and white uniforms arranged in the cabinets surrounding it.

The doodlebug however, is one of only a handful of large objects in the Holocaust gallery and yet this does nothing to diminish the gravitas – a single shoe in a glass case from the remains of Birkenau, or a singular brooch left by a man to his family are perhaps more effective and emotionally wrenching. The lack of colossal white models and mounds of possessions are replaced by a more intimate excess such as the cabinet of documents demonstrating the amount of paperwork needed to emigrate from Austria, or the wall of ‘Domestic Situations Requires’ pages from The Times highlighting the increase of those attempting to flee from 1938 through to 1939.

There are definitive museological choices that are worthy of note also. The galleries are light, airy and blue – a far cry from every other Holocaust exhibition the world over – symbolic of the fact that the majority of the Holocaust occured in daylight, in public spaces and with the knowledge of those around. It is only when you move into spaces off the main route dedicated to slave labour camps and extermination camps that the mood and lighting changes ever so slightly. The lightness and relative plainess of the spaces will surely be a point of contention for those who loved the old galleries and yet, for those who appreciate the difference it will make the majority of the contents even more disturbing when one realises that it took place for all to see.

One choice that certainly has an effect is the exclusion of survivor testimony until the last room. Throughout the gallery the conscious choice was made to only quote contemporaneously, to only show photographs and film from the time, combined with the life size translucent photographs of the individuals mentioned. The effect is thus more powerful when you move out of the section on liberation and displaced persons camps, to hear testimony of those who survived.

A quiet space for contemplation and reflection.

And yet despite the words of the survivors not appearing as prominently throughout the gallery they have still been included and consulted throughout. Curator Lauren Wilmott described it as an ‘absolute privilege’ to show Anita Lasker-Wallfisch round the gallery before they open to the public. Anita’s red jumper which she wore in Auschwitz Birkenau and Bergen Belsen underneath her uniform, is one of a number of objects donated by survivors such as Jan Imich, Kitty Hart-Moxon, Freddie Knoller and Eva Clarke.

So where do we go now? Twenty years since the last exhibition opened to the public to raucous praise, Imperial War Museum’s next stage in its redevelopment can be treated with equal jubilation. No Holocaust scholar can envy the task set to the curatorial team of James Bulgin, Jessica Talarico, Lucy May Maxwell, Lauren Wilmott and Rachel Donnelly, as it is impossible. To depict the scale, horror, reality and complexity of a continent wide series of events in a way that is accessible, achievable and appropriate will inevitably miss things or underrepresent some. But the challenge has been met and the task completed – the gallery depicts scale but remains personal, horror without sensationalising, and complexity without alienating or overwhelming.

It is also important to mention that alongside the opening of new Second World War and The Holocaust Galleries in 2021, IWM’s Second World War and Holocaust Partnership Programme (SWWHPP) will support eight cultural heritage partners across the UK to engage with new audiences and share hidden or lesser-known, local stories related to these histories. Over the next three years, the SWWHPP will support skills development in Partner organisations and facilitate loans of IWM’s rich collection across the UK in support of digital and community-based events co-produced with local people and creative artists. The British Association for Holocaust Studies looks forward to the projects that will emerge from this collaboration.

Experiences of volunteering at IWM

Charlie –

In 2018 I was able to intern at IWM in the Digital Engagement Team working on their social media and website content creation. Whilst on my placement I was lucky enough to attend an interview conducted by one of the team with a Second Generation survivor after he donated some of his family’s items to the galleries. On this particular event I met James Bulgin and asked if I could volunteer for the Holocaust Galleries reserarch project next summer. In the summer of 2019 I worked with curators and other volunteers helping to fill the gaps in their primary source research which involved trawling through articles in The Times as well as searching letter collections, diaries and other contemporary sources for quotes to compliment pre existing sections. Although relatively late to the game, with the galleries having already been largely designed and the first half written by the time I arrived, the remaining sections to do were elusive and required greater lateral thinking than perhaps I had encountered before. I am primarily a historian of refugees and thus exploring areas of the Holocaust I was less expereinced with was a challenge but also an opportunity.

I shall forever be grateful to my time working on the galleries at IWM as it gave me the spark for my MA thesis and subsequently my PhD thesis idea. I always toyed between ideas of working in the heritage sector or academia and IWM allowed me to do both and experience both in one setting – what an opportunity!

Hannah –

I first contacted IWM London about the idea of completing a placement there, as would be funded by Midlands4Cities as part of my PhD development. I met with Suzanne Bardgett, Head of Research and Academic Partnerships and former team leader of the first Holocaust Exhibition at the museum. She then introduced me to current Head of Content, James Bulgin who talked me through their new concept for the regeneration of the Holocaust Galleries. I was in awe of their vision, and of course thrilled to be a part of it. I came on board as a voluntary content researcher for six months, as agreed by my funding body, but ended up staying for much longer. Working with the incredible team of curators – James, Lauren, Jess, Lucy and Rachel – was quite simply, a privilege. They invited me to join them on content writing workshops, to presented my own research at the museum, I attended meetings with the graphic design team, events at IWM with Holocaust survivors and trips to visit other museums in London for inspiration. Coincidentally, Vikki Hawkins from the Second World War curatorial team and I attended a conference in Tallinn, Estonia together, during which she discussed the upcoming galleries, and I discussed my PhD thesis.

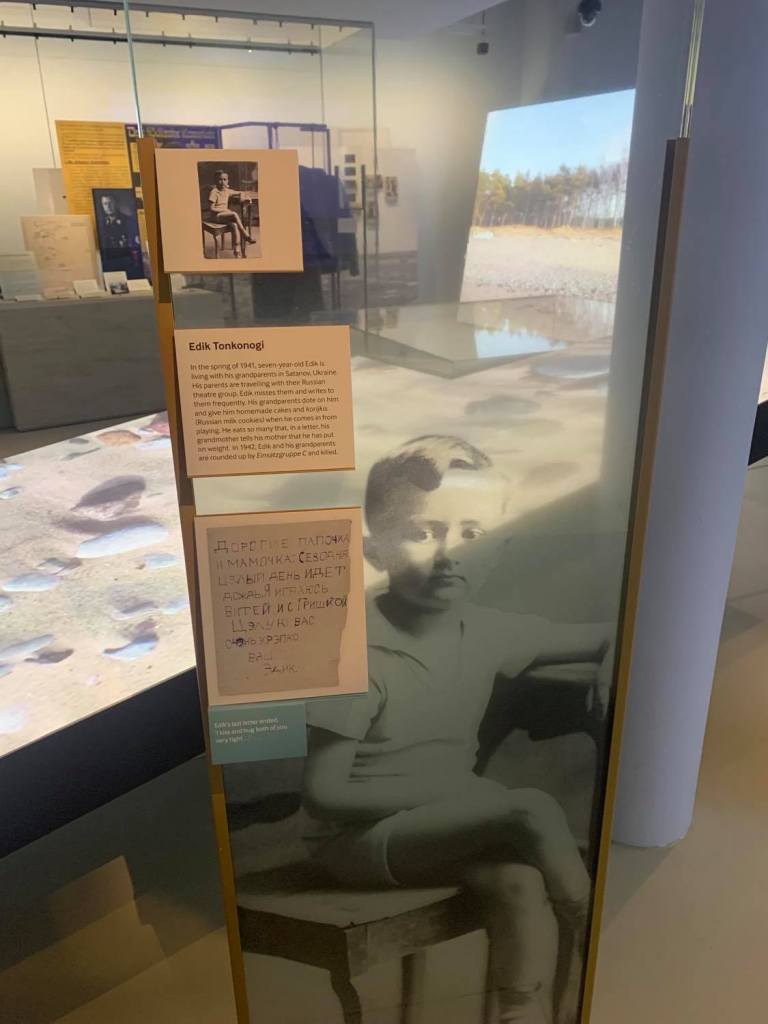

During my placement, I was tasked with all kinds of research duties, including finding photographs of SS perpetrators, photographs of displaced persons, of various “operations” at the beginning of the Holocaust, quotes for the various themed gallery sections, potential former Shtetls across Eastern Europe where footage could be taken – to name only a few. The challenge of finding only contemporaneous documents or sources was difficult at times, yet, I understood the importance of allowing the exhibition to unfold in ‘real time’, and it pushed me to work harder. Some of my most memorable assignments included writing up the process of arrival to killing at the Operation Reinhard camps, as well as understanding the process of sourcing and lending artefacts, which will directly inform my own PhD thesis. Most importantly, I was often asked to finding potential personal stories – for which pre-war or wartime photographs were also available. This included families killed by the Einsatzgruppen squads in the East. As such, I came across the story of Edik Tonkonogi, who lived in Satanov, Ukraine. He wrote letters to his parents who were travelling with their theatre group, on of which is included in the new Holocaust Galleries. In 1942, Edik and his grandparents were rounded up by Einsatzgruppen C and killed. The family, and an example of his letter writing. now has it’s own totem in the exhibition. Similarly, my friend Natali Beige introduced me to her own family narrative when I contacted her for potential stories from Lithuania, which I am moved to say has also been included in the galleries. You can read her story in the section below.

Aside from the friendships I made at IWM, I feel that my placement has helped me develop as both a researcher, and as a person. Unfortunately, the pandemic cut my time short, as did my own PhD commitments. Yet, throughout my time there, I felt heard, valued and respected by the curators – which is not always the case for an intern. The pride I felt in seeing the exhibition in its final stages is almost indescribable. I am so proud to have been a small part of such a huge achievement, and I want to sincerely thank the Holocaust Galleries curatorial team for this opportunity. I will never forget it.

A Family History Commemorated in the new Holocaust Galleries, by Natali Beige

On June 4, 1941, Sara Tatz wrote a letter to her younger brother Gershon, my grandfather, who emigrated from the town Raseiniai in the Lithuanian province to the land of Israel in 1935. The letter is quite ordinary, news from home about family and friends and daily matters of health and livelihood. However, between the lines, a short sentence holds a dark presentiment of the terrible future that awaits Lithuanian Jews: “These days we do not go to the village anymore. Hopefully the times will be peaceful and then everything will be alright”. Sara Tatz’s wish didn’t come true. In less than two weeks, with the beginning of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941, the Lithuanian countryside was radically transformed to the center of unthinkable human atrocities. By the end of December 1941, more than 100,000 men, women and children, among them the entire Tatz family, were dead, shot and buried in hundreds of mass graves.

Before the extermination camps and gas chambers, the killing pits of the Eastern front were the preliminary stage in the implementation of the Final Solution, a stage referred as “Holocaust by bullets”. The destruction of the Jewish communities in Lithuania was top-down Nazi policy; yet, the speed and the scale of the killings were facilitated with the help of local collaborators, neighbours, thus adding another layer of horror to the massacres. Centuries of shared life and glorious Jewish history ended, literally, on the edge of the killing pits.

As in many parts of Eastern Europe, the Holocaust seem to be anonymous mass murder. However, behind the statistics and dry numbers there is a kaleidoscope of faces, voices and stories of countless human beings. The new Holocaust galleries at IWM offers a rare window into their vanished world, into their lives, hopes and dreams. It’s a great privilege that my grandfather’s family is presented here, thus ensuring that their voices and stories, as well as so many others, will not remain anonymous in the dark and will not be forgotten.

One thought on “Review: Imperial War Museum’s New Holocaust Galleries”

Comments are closed.