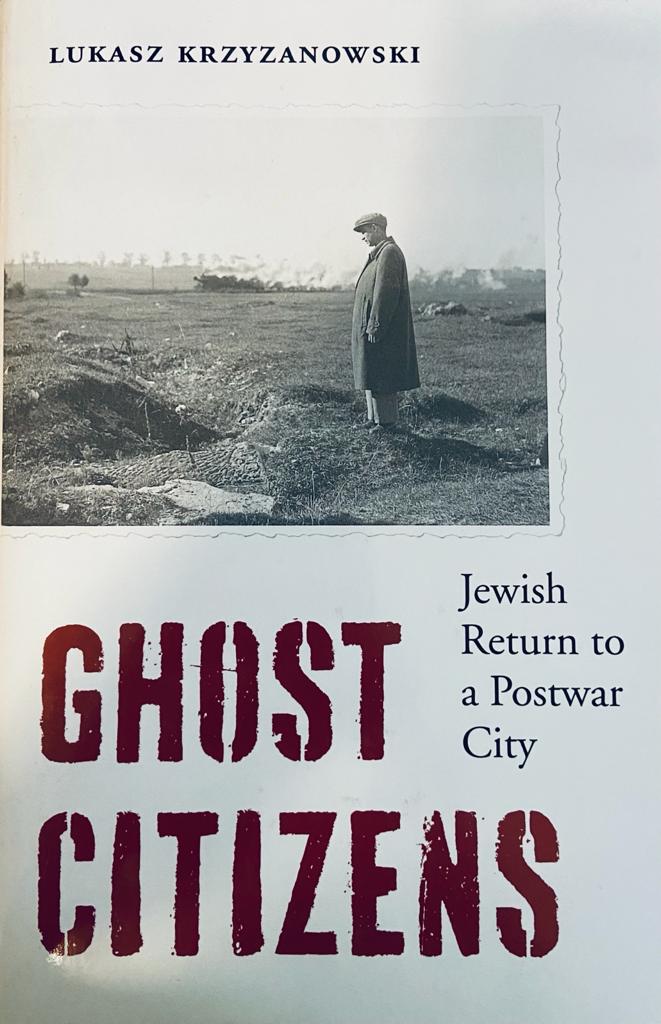

Book review of Lukasz Krzyzanowski, Ghost Citizens: Jewish Return to a Postwar City, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020, 333 pages.

By Daniela Ozacky Stern

With the end of WWII, hundreds of thousands of Jews remained in Europe. They had survived the Holocaust and now had to decide where and how to lead their new lives. Many decided to return to the places they had called home before the war, to see if anyone or anything was left. It was often then that people realized how much they had lost, when they realized that no one and nothing remained. They found themselves in a completely different and unfamiliar reality. The Nazi genocide had left no place unmarked in post-war Poland, and when people turned to the safety of what they knew as “home”, they found strange and hostile territories.

Lukasz Krzyzanowski headshot courtesy Marcin Kucewicz.

Lukasz Krzyzanowski’s book, a translation and expansion of the Polish book published in 2016, traces connections and parallels between the Jewish community of Radom on the eve of the Holocaust and the community of those who returned there after the war. Community is a central motif in the book, with an entire chapter dedicated to it and the title of the book – “Ghost Citizens” – dictated by it. The Jews who came back to Radom after the Holocaust were mostly met with indifference or hostility by the local population. Though they had returned physically, they were treated with suspicion, alienated by a deep-seated grudge held against them, sentiments which soon lead to a murderous climax. These were people who had returned home having lost everything; their loved ones, their families, their houses and property, their physical and mental health. After all they had been through in the camps, they were looking for a home, a place they would belong. But what they found was the complete opposite.

The gulf between Polish Jews and Polish Christians gaped wider than ever in the aftermath of the German conquest. Both populations were horribly damaged by the Nazis, but the experiences of each group were starkly different. The war brought out moral and physical courage in those who risked their lives to help others, but it also exposed abyssal evil, meanness, greed, and the desire to abuse and exploit. The Jews who were branded, confined to ghettos and camps, and sentenced to death under the Nazis were radically dehumanized, expelled from the human community en masse. Moral standards all but disappeared during the war, and into this wasteland came those Jews who had survived the massacre. The motif of homecoming, the “nostos”, especially after the trauma and displacement of war, is a universal experience, intrinsic in human nature. Primarily a physical return, it is often accompanied by a spiritual dimension, and the psychological experience of uncertainty. The book tells the stories of Jews who survived and came back home to Radom, or at least tried to, only to face danger and bitter disappointment.

It is estimated that between November 1944 and the end of 1947 approximately 1,500 Jews who had survived the Holocaust were murdered in Poland in individual assaults and mass pogroms. The most well-known case happened on the 4th of July 1946 in the city of Kielce. A Polish eight-year-old had disappeared around that time, and when he resurfaced, he claimed to have been kidnapped by a Jew. One of the Jews, a young orthodox man and concentration camp survivor named Kalman Singer, was accused of perpetrating the crime, and as anti-Jewish rumors circulated, the public reacted accordingly. Very soon this incited anti-Semitic public unrest and a galvanized Polish throng, armed with sticks and stones, began to target Jews, crying out slogans like “Death to the Jews.” 47 Jews were murdered that day in Kielce, women, and children among them. Around 50 were wounded. This pogrom was the central case study in Fear, a book written by Polish-American historian of Jewish extraction Jan Tomasz Gross. Gross is best known for his groundbreaking book Neighbors, which deals with the role of Poles in the murder of their Jewish neighbors in the town Jedwabne. It is well-known that Poland’s relationship with its past is complicated, especially when it comes to the direct involvement of Poles in violent acts against Jews during and after the Holocaust.

Krzyzanowski, a lecturer at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, has undertaken the important task of tracing the fates of those Jewish Holocaust survivors who returned to Radom. The result is this important book, perhaps one of the most important to come out in recent years on the subject of the Holocaust, which has assumed personal significance for the author of this review. We first met in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington during a research workshop devoted to the Jewish Holocaust in Poland. Many of the participants were non-Jewish Polish researchers dedicated to the study of the fates of Polish Jewry, for which they deserve to be held in the highest regard. Krzyzanowski has devoted many years of his life to studying the fate of Jews who returned to his native city of Radom once the war was over, and the author’s voice is heard frequently throughout the book. He notes that they were ordinary people living through extraordinary times, whose personal stories had yet to be told. He believes there has not been sufficient emphasis on the study of Jewish lives during this critical period and that this part of history has been neglected.

The city of Radom in the Kielce district, which the book examines, in fact serves as a case study of a wider phenomenon of processes taking place in post-war Polish society. I think it is highly interesting and noteworthy that a young non-Jewish Polish researcher should be drawn to the study of Jewry in his hometown, and that he is not alone. Nowadays, extensive research of the Holocaust is being conducted in Poland primarily by non-Jews, and new research and memorial institutions are being established.

The book is divided into four main sections. The first section focuses on the city of Radom, describing its history before, during and after the Holocaust. The second section, “Violence,” describes the destructive events in the post-war city. The third section, “Community,” deals with the inner life of the Jewish population who survived the war and returned to the city, their attempts at self-organizing and memorializing the victims. The final section, “Property,” describes the sad fate of Jewish property during and after the war, and the difficulties in restoring Jewish ownership.

The City of Radom

Radom is an industrial city located about one hundred kilometers south of Warsaw. In the period between the two World Wars, it was home to approximately 90 thousand citizens, about a third of them Jews who spoke mostly Yiddish. Like other cities of the period, Radom experienced a rise in anti-Semitism and nationalism, which influenced the relations between the Jewish and non-Jewish communities. Anti-Semitism eventually began to take the form of physical assaults on Jews and demands to confiscate Jewish businesses and thus to cause financial damage. Radom was not unique in this: in 1936 a murderous pogrom took place against the Jews in the neighboring town of Przytyk, as part of a wave of anti-Semitism which swept Poland in the wake of the death of Marshal Jozef Pilsudski in May 1935. Against the background of the Przytyk pogrom, which occurred the day after Purim on 9 March 1936, the Yiddish Krakow-born poet Mordechai Gebirtig wrote his famous poem “Es brent” – “It is burning.”

Radom was occupied by the Germans on 8 September 1939, and a month later was included in the Generalgouvernement and became the capital of one of its four districts – Radom, Warsaw, Krakow, and Lublin. In accordance with German conquest policy, the two main activities carried out in the area were economic exploitation and the extermination of Jews. Indeed, persecution of Jews in Radom began in the very first days of the occupation, and gradually grew in frequency and brutality. Radom Jews were subjected to forced labor in a number of camps. In November 1939, a Judenrat was established in the city, headed by the industrialist Jozef Diament who, like the heads of other Jewish councils, found himself caught between hammer and anvil – on the one hand, he had to obey German orders, and on the other work towards the good of the Jewish community in the city and other smaller communities in the area that he was responsible for. In April 1941, the non-Jewish residents of two areas in the city were evacuated, to be replaced with Jews, thus creating the two Radom ghettos – the large ghetto and the small ghetto, populated overall by approximately 33 thousand people. The conditions in the ghettos quickly deteriorated. They were horribly overcrowded and there was widespread hunger and disease. As part of “Operation Reinhardt”, the Germans and their allies perpetrated acts of violence against Radom Jews, sending many to extermination camps, Treblinka in particular.

When the survivors returned to Radom, having experienced firsthand the indescribable suffering of the camps, they were met with a reality that was very different from the one they had left behind. The German occupation had split Polish society in two: Jews and non-Jews. The author shows how the differences which had existed before the war became truly abyssal under the influence of all that had transpired during the war. Krzyzanowski devotes a significant portion of the book to describing the pillaging of Jewish property, which was widespread during the German occupation and continued afterwards. And indeed, attempts by Jewish survivors to regain their property are connected in most cases to violence against them. Non-Jewish locals did not welcome the idea of sharing Jewish property with their original owners. More than once, robbery and theft were perpetrated against Jews, and in two instances described in the book in detail, such activities claimed Jewish lives: the Jews being robbed followed the robbers’ orders, yet they were still murdered.

Ludwik Gutsztadt was a Jew who owned a jewelry store in Radom. He had served in the Polish army prior to the war, was in Warsaw during it, and even fought in the Warsaw Uprising which took place during the summer of 1944. In the afternoon of 16 June 1945, after returning with his wife to their Radom house, he was robbed, and even though he handed over the jewelry bag he was carrying, the robber shot him dead in a supposedly unmotivated murder. His wife was left unharmed. Another incident happened on 6 November that same year, when two men in civilian clothes broke into an apartment shared by a Jewish man, a Jewish woman, and two Christian women. The robbers demanded money and valuable property and turned over the apartment looking for it. They then took the Christian women outside and shot the Jewish 30-year-old man, Aaron Hendel, dead. They also shot at the Jewish woman, the man’s sister-in-law, wounding her hand. The murderers were never caught. Krzyzanowski is careful to point out that while the precise reasons for these murders remain unknown, it is certain that in both cases the perpetrators of the crimes knew they were shooting Jews.

The Murder of the Four on Żeromski Street

The most violent incident in Radom took place on the night of 10 August 1945, in an apartment on Żeromskistreet, and was unlike any of the other incidents. Krzyzanowski points out that it was unique in the brutality with which the victims were slaughtered. One of the witnesses, Moses Kirshenblat, a Jew who was apparently the last person to see the victims alive except for the murderers, tells that he left the apartment a little before ten in the evening. The next day he heard news of the murder. One of the atypical things about the murder was that it was not accompanied by robbery as was typical of other cases. Money and other property were left untouched. To all appearances, violence was the sole motive of the crime. The four who were murdered were Aaron Getlach, a 33-year-old first lieutenant in the Red Army of Jewish descent, a recently married couple, 19-year-old Bela Appel and 20-year-old Josef Gutman, and Tanhum Gutman, a uniform tailor who owned a shop and was 34 years old at the time of his murder. He was stabbed with a knife in the throat and stomach, and near the heart. The body of the first lieutenant was found in the corridor, his hands tied behind his back with a bullet wound in the back of his neck. Bela Appel (Gutman), found lying in the corridor with her hands tied, was stabbed with a knife, and shot in the back of the neck. Josef Gutman was shot and taken to the hospital but died of his wounds the next day. Elias Shneiderman was Josef Gutman’s relative and a witness at his wedding. The day after the murder, he arrived in the apartment and found a note with explicit threats that if he and his wife did not leave the city within three days, they would meet a similar fate. The Shneidermans arranged for the burial of the Gutmans in the Jewish cemetery and left the city immediately afterwards. The murder had been carried out quickly and secretively, apparently in less than 20 minutes, and without witnesses. This was in contrast to the demonstrative pogroms accompanied by propaganda, vocal self-justification, and blatant blood libels against the Jewish victims, the best-known of these being that Jews use the blood of Christian children to bake matzohs for Passover. Because of these differences, this Radom murder stands apart from the three large-scale pogroms against Jews in post-war Poland, which took place in the cities of Rzeszow, Krakow, and Kielce. Nonetheless, it seems that intense post-war anti-Jewish sentiments, characterized by fears that Jews were coming back to claim their property, was what caused the violence.

Additionally, it should be noted that the murder in Radom occurred the night before the well-known Krakow pogrom of 11 August, in which a galvanized throng broke into a synagogue, pelted those who were praying inside with stones, set the building on fire, and proceeded to act violently against Jews for more than 24 hours. For this reason, the author concludes that anti-Jewish hatred was the main motive for the Radom murder. The survivors who remained in Radom also saw it as an anti-Semitic act against Jewish residents, and in fact the entire local Jewish community. It occurred amid calls for Jews to leave the city. A little before the event, anti-Semitic pamphlets were handed out demanding Jews to leave, and appealing to non-Jewish locals to deprive Jews of their property and chase them out of the country.

Receiving no protection from the authorities, Jews were forced to protect themselves, and the easiest way to do so was to simply leave the places to which they had just returned. Those who chose to stay or were forced to stay for lack of other options chose to isolate themselves from non-Jewish communities. The isolated Jewish community in post-war Radom was collectively ignored by the non-Jewish residents. These Jews were “ghost citizens” who, though present, existed apart from the society they had returned to. This tragedy is compounded by the loss of Jewish property, confiscated and passed into the possession of non-Jews.

A Microhistory of a Wider Phenomenon

The Poland of today is still a post-genocidal country, and traces of the Holocaust are still apparent there, including current historical and political arguments. Krzyzanowski emphasizes that the suffering of Jewish citizens who walked the streets of Poland during and in the aftermath of the war needs to be seen as congruous with the rest of Polish history. His brave work is a microhistory of an industrial, peripheral city which has not been studied extensively so far, but which serves as an example of the post-Holocaust Jewish experience in Poland. The very welcome English translation now makes the book available to a much wider public. This important research illuminates, in unique and fascinating ways, the dynamics and harsh realities of a traumatized and split post-war society.