Representing Anne Frank in Times of Artificial Intelligence

By Kees Ribbens PhD

Kees Ribbens PhD is a senior researcher at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, and Endowed Professor of Popular Historical Culture of Global Conflicts and Mass Violence at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. Public history, in the broadest sense of the term, is among his key interests. He is particularly interested in the history, memory and representations of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and the role these phenomena play in political and educational contexts.

Today’s societies in the western world desire an accessible past, a past that is close to us. A past that meets our 21st-century needs and must therefore be easily approachable and captivating. A past that is neither abstract nor distant to us. Recognizable individuals can embody that past and make it imaginable, even a phenomenon as inconceivable as the Holocaust. That is why we identify with, for example, Anne Frank: a world-famous icon of the Holocaust. We are familiar with her diary and equally familiar with some portrait photographs made of her. Moreover, there is even a family film with wedding scenes made at the Merwede-square in Amsterdam on July 22, 1941, in which Anne briefly appears, smiling to the camera for about ten seconds. One of Anne’s earliest biographers, the German author Ernst Schnabel, mentioned this footage as early as the 1950s. He was clearly moved by the film fragment and devoted two full pages to it in Anne Frank. Spur eines Kindes[1].

The film became available to a wider public when it was shared on YouTube in June 2006 by ‘AerobeBlue’ and became more accessible once the Anne Frank House released it on its own YouTube channel in 2009. While this grainy black and white footage looks anything but slick, it is authentic and impressive. On this particular YouTube channel alone, the short film has already been viewed more than six million times, proving the need for moving images and for a genuine representation in motion, which is undeniably great nowadays. Yet, the available material cannot satisfy the hunger for moving images of Anne.

Anne Frank Meets Artificial Intelligence

Since late February 2021, the genealogical website MyHeritage.com a commercial high-tech platform founded by the Israeli entrepreneur Gilad Japhet, is offering the possibility of converting photos into moving images using artificial intelligence through an app named DeepNostalgia. This is based on software developed by D-ID, a company that describes its invention as reenactment technology.

According to the genealogical platform, it has already been used 50 million times in less than three weeks after its launch, making the app the number one on the iOS App Store in the UK and the number one free Iphone app in the US. Users register with the site after which they can upload up to five photos – thus sharing them with the company – and have them animated for free. Those who want to use this tool more often need a subscription with features for making a family tree which costs about US $ 17 per month.

Given the initial target group of people interested in family history, it comes as no surprise that many photos of deceased (great)grandparents and other ancestors have been animated. MyHeritage explicitly intended this use, although it seemed to anticipate that other use was possible as well, according to an appeal to users of DeepNostalgia: “Please use this feature on your own historical photos and not on photos of living people without their consent.” As it turned out, the public took the label “your own historical photos” rather broadly. Numerous celebrities from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries soon emerged here (sometimes supplemented by prominent personalities from earlier centuries, portrayed in paintings, drawings and even sculptures). Various websites are now presenting interesting overviews of them.

Images from the Second World War are also included, ranging from portraits of German and British soldiers, to the image of a Polish nurse killed during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising.

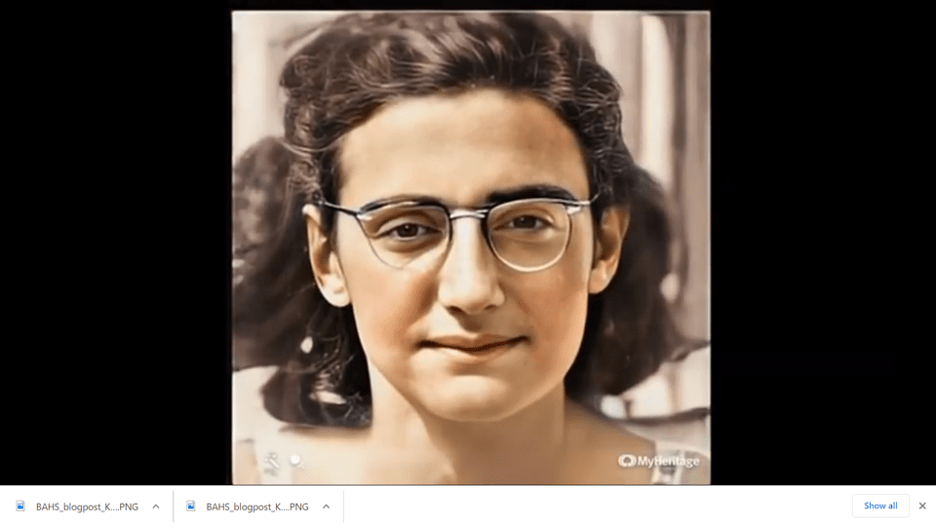

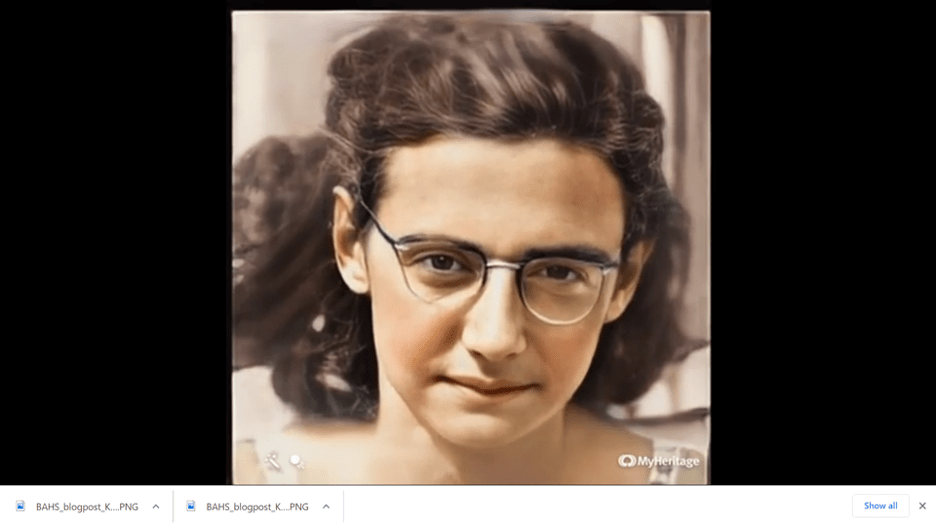

And it didn’t take long for photos of Anne Frank to be processed here as well. The first one in which I saw Anne Frank moving appeared on the American website Reddit.

The results are described as “a little uncanny” but the contributor (i.e. the uploader who made use of the app) apparently sees “the humanity of Anne reflected” in these images, which would emphasize “what she was: a little girl, a child who was legally murdered” according to the uploader on Reddit. On 1st March 2021, the first results also appeared on Twitter, which featured short clips of barely 15 seconds in which Anne turns her head, moves her eyes and also seems to open her mouth. The comment simply states: “See Anne Frank in motion”. A second video was then uploaded to Twitter during the same day, but based on a different photo.

Considering this, I suggest that it is alienating and even somewhat frightening to see someone, whom we know primarily for being persecuted and murdered, so sharp and seemingly alive on a screen. But apparently this animated representation did not yet bring her close enough to meet our 21st Century standards, as an animated video based on a colourised photograph subsequently appeared on YouTube.

Continuing my search across the internet for such videos, I also came across two combined ones in which not only Anne but also her sister Margot – of whom no known moving images exist – was colourised and brought into motion. The video appears to have been produced shortly after the introduction of DeepNostalgia.

In all cases, the photographs that served as starting point for these ‘films’ were taken before Anne went into hiding with her parents and sister in July 1942, and thus before she ended up in the concentration camps two years later. In that sense, they show an Anne who was still unaware, not only of the experiences that would ultimately make her so well-known after her death, but also of the variety of representations that would contribute to shape her posthumous remembrance.

The reason that the animated images are restricted to Anne’s time at the Merwedeplein in Amsterdam cannot be explained by a certain hesitation. The most likely and important explanation lies in the fact that no photos are known from a later time period. After all, imagery from other victims during the later stages of Nazi persecution had already been uploaded to DeepNostalgia. For instance, an Iranian photography enthusiast published one of the Auschwitz registration photos, already edited by the Brazilian photo colorisation specialist Marina Amaral, on Twitter. Remarkably enough, this tweet used the hashtags #ana_frank and #Holocaust but made no mention of the name of the portrayed victim, a Catholic Polish girl named, Czesława Kwoka.

Need for Visual Literacy in Holocaust Memory

The rapid rise of artificial intelligence, and the easy access to this form of technology via websites and phone apps, has resulted in large-scale use of such animation sites within a very short period of time. Responses in the media concerning the results of the edited images are mostly positive, though occasionally viewed with some astonishment, particularly because some animations are experienced as unsettling; not least because the knowledge that they are artificial and manipulated images is difficult to reconcile with the feeling that these images appear to be lifelike impressions. The question of whether it is problematic that both the photographer and the person portrayed did not – and could not – consent to this editing of the image is usually not addressed, despite raising many ethical issues.

The fact that this technology is also applied – albeit modestly so far – to visual material related to the Holocaust testifies to the widespread interest in this particular genocide. But more often than not, the reactions in this area seem to be slightly more restrained. Cambridge historian, archaeologist and IHRA delegate Dr. Gilly Carr tweeted an animated and colourised portrait of Auguste Spitz, a Holocaust victim from Guernsey who was killed in Auschwitz, stating “I feel unease about showing this – is it right to animate old photos of Holocaust victims?”

Such a question does not seem fitting for a simple yes or no answer. Above all, we must realize that the long-term impact that this new technology will have on public engagement with the Holocaust, particularly with (images of) individual victims, is still unknown. The form of these images also changes as they appear in a new context. Historical photographs which are animated, claiming to remain authentic images, in fact become false videos. The ‘deepfake’ images in the examples mentioned above can be identified by the MyHeritage logo in the lower right corner of the screen, provided the viewer pays close attention. But to anyone who realizes how widespread and user-friendly image editing technology already is, will understand that it would only require a small effort to make such references to contemporary intervention virtually invisible. Image manipulation as such is not new, but it is likely to become increasingly difficult to recognize what is ‘authentic’ or original.

At the same time, these new possibilities do appeal to a wider range of people, people for whom this past suddenly seems much less remote and who are actually touched by it. Are they, and will they, remain aware of the technological adaptations of the original image? Does this play a role at all in their appraisal? These aspects complicate an unequivocal assessment of what is currently (and rather optimistically) labeled as ‘DeepNostalgia’. How will historians, heritage specialists and other professionals relate to these new options, which were once unattainable? Do museums dare to ‘lag behind’ the current trends, when images widely circulating in cyberspace look less static and thus less distanced than what is shown in their exhibits? The importance of visual material in passing on historical experiences and narratives is not diminishing at all, on the contrary. But the need for critical visual literacy, which distinguishes between what is real and what is fake, but which also recognizes the perceived need for immediacy, is growing urgently.

Conclusively, another background issue also plays a role. A certain fear exists that these new adaptations, in particular when they are not recognised as being manipulated, can benefit Holocaust deniers:

Revisionists and deniers can potentially exploit the fact that the authentic character of the underlying photographs in contemporary animations is not mirrored in the final animations. Therefore, they might see this as a stimulus to dispute the authenticity of original photographs – just as they like to contest all sorts of historical sources on dubious grounds to cast doubt. While the potential uses of new presentation methods should not be held hostage by such fears, the identification of such risks must be included in a further reflection on digital and visual literacy which, as we see in cases such as ‘DeepNostalgia’, is urgently needed.

An initial version of this blog, based on a Twitter thread [@HistK], was published in Dutch at: https://niodbibliotheek.blogspot.com/2021/03/holocaustverbeelding-in-tijden-van.html

[1] Ernst Schnabel, Anne Frank. Spur eines Kindes. Ein bericht (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Bücherei, 1958) 45-46. Thanks to Remco Ensel for reminding me of this footage.