By Peter Morgan

Peter Morgan was a secondary school History teacher for 21 years and has worked in Holocaust education with the Centre for Holocaust Education at UCL and the Holocaust Educational Trust. As part of his PhD, he is currently researching British discourses about the Armenian genocide 1915-23. He is based in the School of Humanities and the research cluster for ‘Understanding Conflict: Forms and Legacies of Violence’ at the University of Brighton. Part of Peter’s work has been analysing the way in which there was a new discourse on the mass killing of civilians that foretold the modern definitions of genocide and ethnic cleansing – one which was later quickly forgotten by the mid-1920s due to realpolitik, arguably with tragic consequences for European Jewry. Not only was it largely forgotten; the discourse also contained some alarming features in terms of British identity and complicity in 20th century methods and rationales of the mass killing of civilians. As such, this research demonstrates the importance of studying the Holocaust within a wider context of modern genocide.

My PhD research on the contemporary British discourse on the Armenian genocide has strengthened my growing conviction that the Holocaust was not a singular and unique event of genocide but one highly significant episode in a series of 20th and 21st century genocides. Genocides with much in common and genocides possibly that have some causal links. One of the reasons for this argument is that the Holocaust as a whole can arguably be broken down into three very connected but separate genocides. The first is the ghettoization and starvation of Jews in Nazi occupied Eastern Europe and the mass killing by bludgeoning and shooting of hundreds and thousands of Jews there, particularly in the Soviet Union and Romania (carried out independently by that regime). It was only towards the end of this genocide in terms of its most active phase (and it did continue until the end of the war) in the autumn of 1941 that a concrete formulation of a complete ‘final solution’ developed. The second genocide revolves around Operation Reinhard and the destruction of Polish Jewry during 1942 and indeed this can be seen as the most complete genocide in history. It is only the third genocide which revolves around Auschwitz, and consists of an attempt to destroy the main part of Jewish communities in both Western and Eastern Nazi occupied Europe using one death camp but where significant numbers of Jews were selected for work. It culminates (in what could be seen as a separate event in itself) in the genocide of Hungarian Jewry in the summer of 1944. This is not now seen by some leading scholars as part of a final ‘Final Solution’ but a genocidal event which largely resulted from a set of localised circumstances rather than a general master plan and thus differed from the fate of Jewish communities in other parts of Europe. Scholars such as Longerich, Gerlach and Cesarani suggest that the ‘final solution’ never stopped developing due to changing circumstances and wartime realpolitik and Mark Levene has recently made a very strong case for the Holocaust being made up of several genocidal episodes.

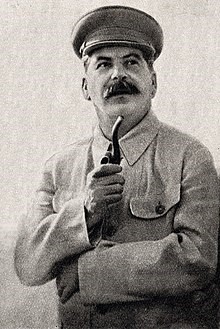

Therefore, this makes it more possible to compare the Holocaust with other modern genocides and lets us see more easily the nature of modern genocide as a long term phenomenon. For example, the genocidal nature of the Nazi ghetto system and its function in immiserating and starving large populations and making them much more vulnerable to disease and annihilatory epidemics. This can be usefully and appropriately compared to Wilhelmine German policy in South West Africa and its use of concentration camps regarding the Herero and Nama tribes. It can also be set alongside the Ottoman deportation of Armenian communities to concentration camps in the Syrian Desert. Stalin’s forced relocation of Soviet minorities such as the Chechens and Ingush is also of note.

The use of manmade famine and starvation and decision making concerning the distribution of life giving resources is of great significance. The manner in which deliberate starvation is a feature of the Herero, Nama and Armenian genocides, and also of Soviet policy against the so called Kulak class in the early 1920s, and the Ukrainians in the early 1930s puts Nazi food policy into a longer term historical context. The idea behind the 1941 Generalplan Ost and its intention to starve 30 million Soviets of all nationalities and religious/ethnic groups perhaps allows the historian to see a 20th century trend in this type of genocidal action (see Tim Snyders, Bloodlands). That this would have impacted at the same time as the 1943 Bengal famine and the racialized British discourse that accompanied it adds to this. Moreover, the longer term could be said to involve the dreadful famines of the late 19th century. Mike Davis in his Late Victorian Holocausts has demonstrated a significant degree of colonial intentionality with racial rationales regarding these. The use of politicised manmade famine after WW2 emphasises such arguments, most notably during Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Furthermore, it raises very uncomfortable questions as to the continued existence of famine in the modern world as a result of huge inequalities of wealth as well as civil war and foreign intervention. Eritrea in the 1980s and Yemen presently spring immediately to mind.

The role of famine in colonial systems, which decided on distribution of aid and food on a racial basis as well as economic systems of free trade and non-intervention arguably, takes us back to the Nazi genocides of WW2. One aspect of Generalplan Ost was the intention to clear the Russian countryside to make way for Himmler’s dreams of Aryan German peasant communities. The Slavic survivors to be utilised as a helot class. The SS Schwarzekorps magazine talked in terms of ‘Go East Young Man’ and Hitler’s table talk was littered with references to what inevitably and in his view rightly happened to the Native American Indians so the USA could become one of the bread baskets of the modern world. The Ukraine and further afield in the black earth zone was to play the same role in a German system of autarky. Furthermore, British India and its famines was another model Hitler looked to. The Lives of the Bengal Lancers has been referred to as Hitler’s favourite film with its paradigm of how a white racial elite numbering in its thousands could lord it over a huge country with a population of tens of millions.

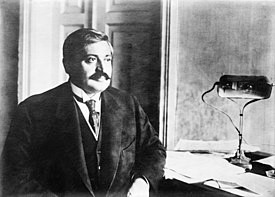

The genocides of Soviet and Romanian Jewry in the Einsatzgruppen shootings and related events involving the Romanian authorities can be compared to many incidences of massacre elsewhere in the modern world. Particularly when viewed as part of a policy of wider intent regarding whole ethnic, religious and political groups. This is especially the case in terms of the Armenian genocide and the role of the Special Organisation forces. The Ottoman exploitation of the conflict between Kurds and Armenians as well as other Christian minorities bears comparison with the Nazi use of Baltic and Ukrainian national groups against Polish and Soviet Jewry during the so called ‘Holocaust by bullets’.

It is during the genocide of Polish Jewry in the Reinhard camps of 1942 that we arguably see a much greater degree of singularity and uniqueness. There is no doubt that the creation of specifically built death camps and a standard operating procedure of killing every man, woman and child that could be found is of huge historical significance. Likewise, a continent wide genocide, which increasingly used one major killing site at the centre of continent wide network of persecution and destruction with specifically built structures that included undressing rooms, gas chambers and crematoria (Tim Cole describes Auschwitz as a node in a continental network). But so too is the significance of von Trotha’s extermination declaration in 1904 and the whole concept of a genocide decision as part of a military campaign and colonial enterprise. Such a development in modern government can be traced back further to Tasmania in the first half of the 19th century (see Tom Lawson’s The Last Man). Hugely significant also is the centrally organised extermination and deportation programme to homogenise the Ottoman Empire so that no area had more than 5% of non-Muslims living there (see Taner Ackam and Raymond Kevorkian). Like the Rwandan genocide it may very well be the case that the killing would have developed to a point where the goal was total extermination had not events intervened. If Nazi Germany had won WW2 that goal would most likely have been readopted again after its suspension at the turn of 1942-3. Therefore, comparability on this issue is perhaps appropriate and raises the possibility that the true uniqueness of the Holocaust was the gulf between the perpetrators perception of the threat and the reality.

Greatly significant too is the development of man-made famine as a weapon against political and ethnic enemies in Soviet Russia and Nazi occupied territories. As is how one consequence of western colonialism was an explosion of violence which saw up to 800,000 murders on ethnic grounds in the space of ten weeks in Rwanda. Probably an unprecedented rate of death in any genocide. Finally such an analytical and historical approach, placing the Holocaust in a much wider and longer term context of modern genocide equips the present day to deal with such events in Myanmar and Darfur and China’s treatment of Muslim minorities more effectively.