Berfin Çiçek is a graduate student from Koç University in the departments of English Language and Comparative Literature and Sociology. She will begin studying at Sabancı University at the department of Cultural Studies as a graduate student in September. She was an exchange student in the United States of America and Hong Kong. She has been the teaching assistant of Assist. Prof. Özen Nergis Dolcerocca for 3 years at Koç University. She is currently working as an intern for editing the writings of Caroline Koç, Koç Holding Management Board Member. She wrote an Honors thesis titled “Telling the Memories of a Massacre: Trauma and Testimony from Dersim’s 38” which was accepted to be presented at conferences in the State University of New York and Princeton University. She also published a critical writing at Brio Literary Journal of New York’s University. She presented at BAHS’ online workshop. She is going to present a work at Turkologentag 2021 “The Fourth Convention of Turkic, Ottoman and Turkish Studies”. She reads Turkish, Zazaki, English, German, and French, and learns Persian at the moment

Last month, the British Association for Holocaust Studies held an online workshop entitled “Sources of Memory and the Holocaust: Contemporary Research, Challenges and Approaches”. As a part of this event, I was honored to present my research on “Comparative Memory Studies and Testimonial Narratives: Possibilities, Advantages and Drawbacks”. In this blog post, I would like to share some keynotes from my observations of the workshop, and from my own research subject. In a sense, then, this form of writing is self-reflective, and about the research process itself. To begin with, the first step was to look back upon the wide range of established studies on testimony and trauma, thus leading me to utilize the examples from Holocaust studies.

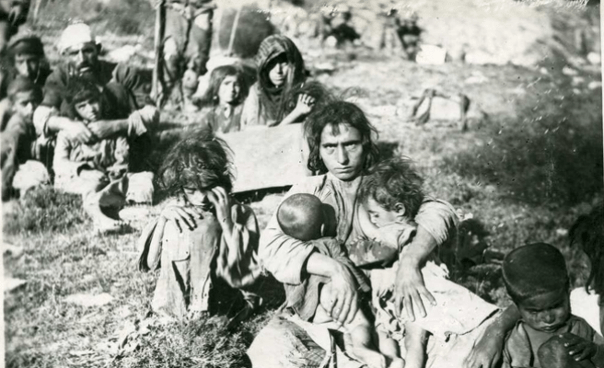

First of all, I must mention that my research focuses on the Dersim massacre, which took place in Turkey in 1938. The reason behind this massacre, as executed by the Government, was to eliminate the tribal community of the Dersim province and convert the Kırmanj-Zaza people of Dersim, which today is the modern-day city of Tunceli, to Turkish-Islamic values of the newly founded republic. Although testimonial resources concerning the Dersim massacre are limited, during my research on the relationship between trauma and testimony, I benefited from works by Dori Laub, Cathy Caruth and Shoshana Felman, so that I could better understand the theories of trauma and ways to read and analyze testimonial narratives. The resources that I used include Dori Laub’s “An Event Without a Witness: Truth, Testimony and Survival”, “Bearing Witness or the Vicissitudes of Listening”, “Truth and Testimony: The Process and The Struggle”, Cathy Caruth’s Trauma: Explorations in Memory, “Unclaimed Experience: Trauma and the Possibility of History”, and Shoshana Felman’s “The Return of The Voice: Claude Lanzzmann’s Shoah” from her book Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History. By using international research within the field of Holocaust studies, this provided me with the opportunity to gain different perspectives of reading testimonials, while Turkish sources were limited.

One reason the main reasons for the lack of resources that help to investigate the Dersim massacre is that, unlike the Holocaust, this violent event is not politically confronted and therefore, the massacre remains in the consciousness of the descendant generations of Dersim[1]. The few contemporary testimonials that do exist are translated from Kırmanjki by small number of anthropologists. These are compiled by Cemal Taş in Dağların Kayıp Anahtarı; Dersim 1938 Anlatıları, Emirali Yağan in Dersim Defterleri; Beyaz Dağ’da Bir Gün and Kazım Gündoğan in his documentary and book titled Dersim’in Kayıp Kızları; Tertelê Çênêku. Yet it is also imporatant to be aware that during this period, Kırmanjki was forbidden to use and, as a result, the number of people who speak Kırmanjki today is very low. This is a big disadvantage for those researchers who want to read the testimonies and talk to the victims. Of course, most of the victims are elderly, and many of them do not speak fluent Turkish or any other languages.

To clarify what I mean by the possibility of testifying, as noted in the title of my talk, the main question that comes to mind is whether or not to testify is the first step for confronting one’s traumatic experience? While some trauma theories assert that it is impossible to retell trauma, the small details in the testimonies such as alluding to the symbols of folk tales, are important to focus on, in order to understand the victim’s revealing of the traumatic memory.

Narratives of old oral folk tales is common among Dersim survivors, and are significant for the testimonies. Although some researchers tend to suggest that trauma is not narratable, it is important to keep in mind that folkloric symbols give the victims a sense of hope and regaining a sense of existence. It helps to preserve their memories, which in turn connects them to their everyday lives by taking a step towards healing the trauma. By asserting the impossibility of transmitting the traumatic experience, these researchers suggest that trauma is a fact that would deprive the victims of their sense of time, space and being. Its tormenting impact would make it hard for the victim to testify, and in turn for the listener to understand what the victim meant when he or she addressed something that seem irrelevant to the experience at hand, but actually that small detail would reveal something hidden in the consciousness.

In that regard, Holocaust studies have enabled me to learn how to properly read testimonials by focusing on more subtle details of the traumatic experience. For example, non-human memory[4] was one of the key terms that I came across whilst dealing with the Holocaust studies. While this term addresses the types of testimony recordings such as video recording, it also enables me to understand the significant role of physical objects and space in the reshaping of the victim’s memory in the post-war period. Therefore, the attributions to terminologies such as non-human memory can differ and lead to diverse meanings and usages by the young researchers. Moreover, Holocaust studies contributed to my research in the sense that Dori Laub’s analysis is an exemplary study of how such a research can be done, and I suggest that such studies lead the way for developing future testimony research, in order to reveal the experiences of other historical atrocities and massacres.

One advantage of doing comparative research through Holocaust studies, is that it leads to the development of new theories and new perspectives that one could apply to other examples of mass violence, when reading the testimonials.

For instance, the difference between historical consciousness and collective memory -as suggested by the anthropologist Özlem Göner- has enabled me to understand that the lack of political confrontation was, indeed, problematic for conducting research on the Dersim massacre. As a result, political non-confrontation or denial of the massacre has caused a condition of “rootlessness” for the victims. Regarding this “rootlessness” and Dersim identity, Özlem Göner asks what can preserve the shaping of an identity “in the absence of official historical mnemonics”[6]. She introduces collective memory as a controversial term and defines the conceptualization of time and space in relation to historical consciousness. Referring to Maurice Halbwachs, she asserts that individual memory is social; it is produced and changed within different social settings. Collective memory, on the other hand, is produced by groups, and recognized by these groups. In order to apply this meaning to her theorization of the Dersim massacre, she asserts that this particular memory differs from the collective memory of the Holocaust, because the history of the Dersim massacre is not officially recognized and thus the narratives of its memory depend on the life stories and fragmented testimonies which are conveyed to the grandchild generation. Therefore, private memory spaces become the only domain in which the witnesses and those affected by the massacre are in touch with each other.

Göner asserts that, in the absence of the “organized memory accounts”, the silence of the massacred community is in fact broken by the life stories, testimonial narratives and the folk songs of those who survived. These folk songs are called ağıt, and they are told when something painful such as the death of a clan member. So, the memory provided in the Dersim testimonies is in fact social, and even cultural because the recollection of their experiences are triggered by symbols such as names, landscapes, icons, images, stories, and everyday interactions with other victims.

After realizing the difference between the collective memory and historical consciousness of the Dersim massacre, the term of intergenerational post-memory gained significance in my research, as the testimonials, remaining photographs, and familial relationships created have directly transmitted memory among the younger generations. This realization, and my acknowledgement of different terminologies has helped to build bridges between established research and my own work on the memory of Dersim. It became obvious that, in comparing my study to those within the field of Holocaust studies, it led me to multidirectional ways of memory research.

In their introduction to The Social Life of Memory: Violence, Trauma and Testimony in Lebanon and Morocco, Norman Saadi Nikro and Sonja Hegasy explains this multidirectionality of comparative memory studies. They quote from Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory: “Comparison, like memory, should be thought of as productive -as producing new objects and new lines of sight- and not simply reproducing already given entities that either are or are not like other already given entities”[7] Therefore, benefiting from previous research on testimonials does not repeat already existing facts about the massacres, rather, they contribute to build a collective and comparative framework within memory studies. For instance, the use of mythical symbols and inclusion of folk tale elements in the narratives of Dersim victims are examples of how people of different cultures differed in the way they testified.

One of the testimonies from Yağan’s book features a testimony which mentions a folk tale about a bird named “pepux”. The story of this bird narrates the metamorphosis of a young boy who turns into a bird out of guilt for blaming his brother for eating all the food. While for those who are not familiar with the trauma theory might think that the retelling of this this story only repeats the existing cultural symbol for which it stands, I am aware the fact that it actually symbolizes the guilt and self-blaming of the victim, which is common.

To conclude, in my experience I can confirm that it is difficult to conduct comparative research on lesser known massacres, especially in countries where it is almost a taboo, and talking about the event is transgressing the rules of the governements or their nationalist beliefs. Nevertheless, by using the wide variety of studies present in the discipline of Holocaust studies, researchers concerned with other violent historical events can continue to use this as an examplary framework for the future, and to communicate with its strong network. Although there might be historical and temporal differences between the events and narratives, established research is the backbone for the new young researchers who, using existing works, can develop their own innovative conclusions and observations.

[1] For further reading on this subject in English, see: Özlem Göner’s . “Histories of 1938 in Turkey: Memory, Consciousness, and Identity of Outsiderness” in International Review of Qualitative Research, Vol. 9 No. 2, Summer 2016; (pp. 228-260) DOI:10.1525/irqr.2016.9.2.228.

[2] For further images, see: https://www.rudaw.net/turkish/kurdistan/151120166

[4] See: Dori Laub’s “Holocaust Survivors Film Project.” <http://fortunoff.library.yale.edu/about-us/founders/>

[5] See: Cemal Taş’s “Introduction” to Dağların Kayıp Anahtarı. Houses built for the soldiers in Dersim during the massacre.

[6] Özlem Göner’s . “Histories of 1938 in Turkey: Memory, Consciousness, and Identity of Outsiderness” in International Review of Qualitative Research, Vol. 9 No. 2, p. 230, Summer 2016; (DOI:10.1525/irqr.2016.9.2.228.

[7] Saadi, Nikro N, and Sonja Hegasy. The Social Life of Memory: Violence, Trauma, and Testimony in Lebanon and Morocco, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 13, 2018. Print.

[8] See: Cemal Taş’s Dağların Kayıp Anahtarı page 270.

[9] See: Cemal Taş’s Dağların Kayıp Anahtarı page 70.

[10] Chapters from Cemal Taş’s book including the name of the victim, place, and time of the testimonial record.