By Dr Steven Woodbridge

Dr. Steven Woodbridge is Senior Lecturer in History at Kingston University, Surrey, and has published articles and book chapters on both the interwar and contemporary extreme right.

In April, 2017, the American Historian of Jewish History and Holocaust Studies, Deborah Lipstadt, in a powerful address delivered at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, recalled her experiences of a legal case for libel brought against her by the controversial Holocaust denier David Irving (an action which he lost). Early on in her talk, Lipstadt pointed out that the Holocaust has ‘the dubious distinction of being the best documented genocide in the world’.

However, as Lipstadt (and numerous other academic experts) have also had to acknowledge, ‘truth and facts are under assault’ (as she put it) – the contemporary far right have made denial of the Final Solution into a near-global industry in the last decade or so, and it remains vital for professional historians and other experts to critically challenge this disturbing trend.

In hindsight, some of the early origins of the extremist attempt to undermine, censor and selectively re-write the historical record for crude ideological purposes can be traced back to notorious far right activists such as Arnold Leese in Britain. Leese (1878-1956) was arguably one of the most palpable examples of a British version of Hitler to have appeared in the country during the 1930s, having created the rabidly anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi ‘Imperial Fascist League’. He had even advocated mass extermination of Jews by gas chambers as early as 1935.

Regarded by State authorities as a potential collaborator in the event of a German invasion of Britain, Leese had been arrested in 1940 and spent much of the war interned in Brixton prison. Yet, when released in 1944 on grounds of ill-health, far from having changed his mind about Nazism, Leese emerged from incarceration even more convinced that his ‘racial fascist’ views of the world were still as relevant as ever.

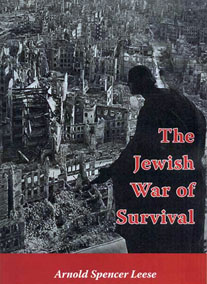

In fact, in June, 1945, within just a few months of the shocking discovery by Allied troops of the full scale and sheer horrors of the German Nazi extermination camps, and very shortly after the conclusion of the war in Europe, Leese announced to readers of his new monthly publication Gothic Ripples that he had written a book on the conflict entitled The Jewish War of Survival. As far as he was concerned, the war had been a ‘Jewish’ endeavour, fought for Jewish interests. Just a month later, evidently with the Third Reich in mind, Leese revealed in Gothic Ripples that he believed that ‘the finest civilisation that Europe ever had has been wiped out of existence by the Allies in a Jewish war’.

During the course of the remaining months of 1945, Leese went on to offer further inflammatory and racist views by criticising the war as the product of what he called the ‘Revenge Instinct’ of the Jews. Moreover, as damning evidence was gathered for the official commencement of the Nuremberg Trials in November, 1945, Leese labelled some of the witness statements as ‘Belsen Bunkum’ and also dismissed the Nuremberg hearings more generally as ‘purely a Jewish and Masonic’ affair, which was, in his estimation, ‘only explicable by the Jewish control of “Democracy” and Bolshevism’. Indeed, as Leese viewed it, the trial was being conducted ‘without the slightest legal authority’.

Tellingly, though, Leese appears to have shifted his stance somewhat during the course of the Nuremberg hearings. While he had initially referred to ‘Belsen Bunkum’ and also to ‘hate-propaganda’ against the Germans, his attempts to undermine and dismiss the trial did not take the form of outright denial of the mass murder of Jewish inmates in the camps, but began to increasingly take the shape of a more ambitious and elaborate conspiracy theory, whereby his early claim that it was the product of Jewish ‘revenge’ was given more and more emphasis. Significantly, Leese did not try to deny that mass extermination by the Nazis had taken place, mainly because (as he admitted) he plainly approved of Hitler’s attempt to deal with the so-called ‘Jewish Menace’. Rather, Leese sought to undermine the credibility of the trial by portraying it as ‘unjust’, not neutral and an act of ‘naked Jewish Revenge’.

This conspiracy theory involved rewriting and distorting the nature of the Second World War, an undertaking which Leese had begun before the Nuremberg trials had started and which was set out in considerable detail in The Jewish War of Survival, a copy of which Leese even managed to send to the Defence Counsel for Hermann Goring, which they accepted. In Leese’s warped interpretation of the key wartime events, the conflict had allegedly been fought in the interests of ‘Jewish Money Power’ and the ‘Dictatorship of the Jew’, while Hitler had actually wanted ‘Peace with Britain’.

This zealous pursuit of a conspiratorial interpretation of history was continued in rather tedious and repetitive form in many of Leese’s post-Nuremberg writings, firmly rooted in an ideological crusade to persuade his supporters and other gullible citizens that the official Allied version of the war had been the product of fraud and propaganda, all the while manipulated by Jewish puppet-masters. Revealingly, by the early 1950s, Leese had reverted back to his ‘Belsen Bunkum’ approach and adopted a more explicit version of what we would clearly recognise today as Holocaust denial. In a 1953 edition of Gothic Ripples, for example, Leese referred to what he called the ‘fable of the slaughter of six million Jews by Hitler’, and denied the truth of the Holocaust.

Arnold Leese’s writings remained for many years banished to the disreputable margins of the world of fringe conspiracy theory and far right politics but, in recent times – especially with the emergence of the internet from the mid-1990s onwards – Leese’s early versions of Holocaust revisionism and denial have re-emerged into the light of day once again and, unfortunately, have been ‘re-discovered’ by a new and younger generation of extreme right-wing activists. In particular, The Jewish War of Survival has been reprinted on a number of occasions by far right publishing houses, while Leese’s other writings have become readily available in numerous forms across the internet. This is why the books of Deborah Lipstadt and other like-minded scholars will remain essential tools in the service of historical truth, invaluable aids in educating the public about the realities of the Holocaust and the consequences of intolerance and racism.