Ellis Lynn Spicer

Ellis Lynn Spicer is an AHRC/CHASE-DTP funded PhD candidate at the University of Kent. Her thesis, under the supervision of Dr Juliette Pattinson examines Holocaust survivor associations, the Jewish community and their effect on identity and memory using an oral history methodology. She is also in the process of researching and curating an exhibition in the Epping Forest District about a hostel in Loughton/Buckhurst Hill that housed survivors in 1946 that is due to open in Summer 2020.

Glenn Sujo highlighted a Buchenwald survivor’s declaration that artwork was a solution to preserving Holocaust memory, through ‘narratives that will let you imagine even if they cannot let you see’ glimpsed in a ‘work of art’.[1] My research in general has utilised artwork from the survivor community through the memory quilts of the ’45 Aid Society. This project, originating in 2015 to mark the seventieth anniversary of the liberation of the members and their coming to England, sought to emphasise their survival and ‘the love of family that lives on’.[2] Whilst many of the society’s survivors’ were no longer alive when the project began, the second and third generation (the children and grandchildren of survivors) had extensive involvement in the creation of the quilt squares commemorating and celebrating the lives of their relatives.

For the survivors’ that were still alive in 2015, they were able to draw on their children and grandchildren as a key form of composure, the enthusiasm of their descendants getting involved in projects such as these giving survivors’ reassurance of their commitment to Holocaust education and commemoration. Whilst a vast proportion of literature focuses on the idea of psychopathology in these survivor groups, less attention has been given to the composure that survivors can gain from the existence of their families, families that they created ‘from scratch’. In these contexts, we can define composure as a general state of wellbeing and equilibrium for these survivors, which can manifest both inside and outside interview contexts. We can glimpse here that the memory quilts of the ’45 Aid Society by their artistic representation of lived experience illustrate composure.

The majority of the squares within the memory quilt showcase happy events, such as family holidays, weddings, birth and family gatherings. Mick Zwirek’s children highlighted the theme of continuing life and the ‘indomitable spirit and courage’ that emerged from the Holocaust, choosing to reflect this through photographs centring on the first and second generation.

’45 Aid Society, The ’45 Aid Society Memory Quilt for the Boys: A Celebration of Life (London: ’45 Aid Society, 2016) p.150.

As we can see above, there is a crucial representation that the union of Mick and Ida had created great happiness and a loving family. Each square was accompanied by a short piece of writing from the creators, where they highlight their ‘smiling faces’. The Holocaust past cannot be glimpsed directly, the focus is on Mick’s birth, his marriage and the family they were able to create. In this vein, the very existence of the second generation is a means of attaining composure, where the past and present ‘coexist’. As a consequence, many survivor parents potentially become more at peace with their traumatic histories.

The symbol of a tree is one that often becomes synonymous with the continuation of life within survivor and second generation produced artwork for the memory quilt project. It has become associated with enduring life cycles and resilience, conveying longevity within those life cycles and the ability to seed new life. The symbol of the tree and other natural phenomenon is most common within the ’45 Aid Society memory quilt squares as survivors begin to reflect on the families they have created and their new ‘family trees’. Janek Goldberger’s square focuses on the motif of a tree, with his children in their accompanying description emphasising, ‘all of the members of our family are on this quilt as leaves on a tree, illustrating how the family has grown and blossomed with our parents at the centre.’

’45 Aid Society, The ’45 Aid Society Memory Quilt for the Boys: A Celebration of Life (London: ’45 Aid Society, 2016) p.47.

Other squares also echo this recurring image, with similar justifications of enduring, continuing life and the notion of blossoming. The tree can also serve as an interesting contrast, as can be seen in Issaak Pomeranc’s square, where his family contrasts the family tree growing on the surface amidst the dark roots of his years of concentration camp experiences.

’45 Aid Society, The ’45 Aid Society Memory Quilt for the Boys: A Celebration of Life (London: ’45 Aid Society, 2016) p.109.

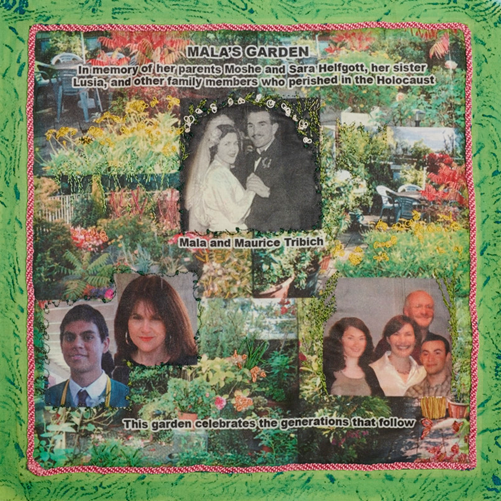

Here, the tree becomes an even more evocative symbol of enduring life, but an image fraught with both positive and negative connotations in line with a survivor’s history. Whilst there is a sense of beginning from weak or decimated roots, resilience is emphasised to a legacy that endures as the tree grows, irrespective of the starting point. Similar to the symbolism of a tree in these contexts is the motif of a garden. Mala Tribich expresses it as thus, ‘My panel shows foliage and flowers on my roof garden….and is both a memorial to my parents and sister Lusia and also a celebration of the younger generations and the season renewal of life’.

’45 Aid Society, The ’45 Aid Society Memory Quilt for the Boys: A Celebration of Life (London: ’45 Aid Society, 2016) p.136.

Here Mala contrasts greenery and florae as a memorial focus but reflective of a positive optimism for the future. This emphasises the dual meanings of symbols found in nature such as the tree, plants and flowers. Whilst some of the symbols can become tinged with mourning and memory of lost loved ones, the symbolism of trees, plants and gardens largely reflect a pride in their families and the ‘blossoming’ of the family tree. These representations act in contrast to the perceived unnaturalness of the Holocaust and going against ideas of nature, harmony and balance. It can be argued that the emphasis on nature is indicative of an attempt to rebalance and find optimism in the endurance of survivors and their families.

Overall, sources such as these, whilst being relatively ‘new’ sources, have so much to add to a historian’s repertoire, particularly those who focus on the postwar lives of survivors. When researching Holocaust survivors’ and their postwar lives, it is important to balance consideration of trauma with consideration of the future, optimism and the desire to ‘get on’. Whilst this does not mean trauma is disregarded, it becomes important for survivors’ to focus on where they draw their strength in the face of their memories. Therefore these memory quilts become an evocative illustration of one way in which survivors have attained composure regarding their Holocaust pasts, through the lens of recreating their families, mostly alone and largely without parental help.

[1] Glenn Sujo, Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory (London: Philip Wilson Publishers and Imperial War Museum, 2001) p.92.

[2] ’45 Aid Society, The ’45 Aid Society Memory Quilt for the Boys: A Celebration of Life (London: ’45 Aid Society, 2016) p.i.